Price cutting has always been rampant in distribution. To use common distributor parlance, firms have an uncontrollable tendency to “take it to the street.” Unfortunately, such price cutting is destructive to profit.

There are two different instances of unnecessary price cutting.

- The first is simply when the sales force caves in on customer price requests.

- The second is when short-term supplier price reductions are passed along to customers.

While they both involve price reductions, they have different profit implications.

This report examines the nature of the take it to the street issues. It will do so from two different perspectives.

- Profit Implications: An analysis of the economic impact of price reductions, whether ongoing or temporary.

- Margin Maintenance Strategies: Approaches for controlling gross margin, even if price cutting is necessary in certain situations.

Profit Implications of Price Cutting

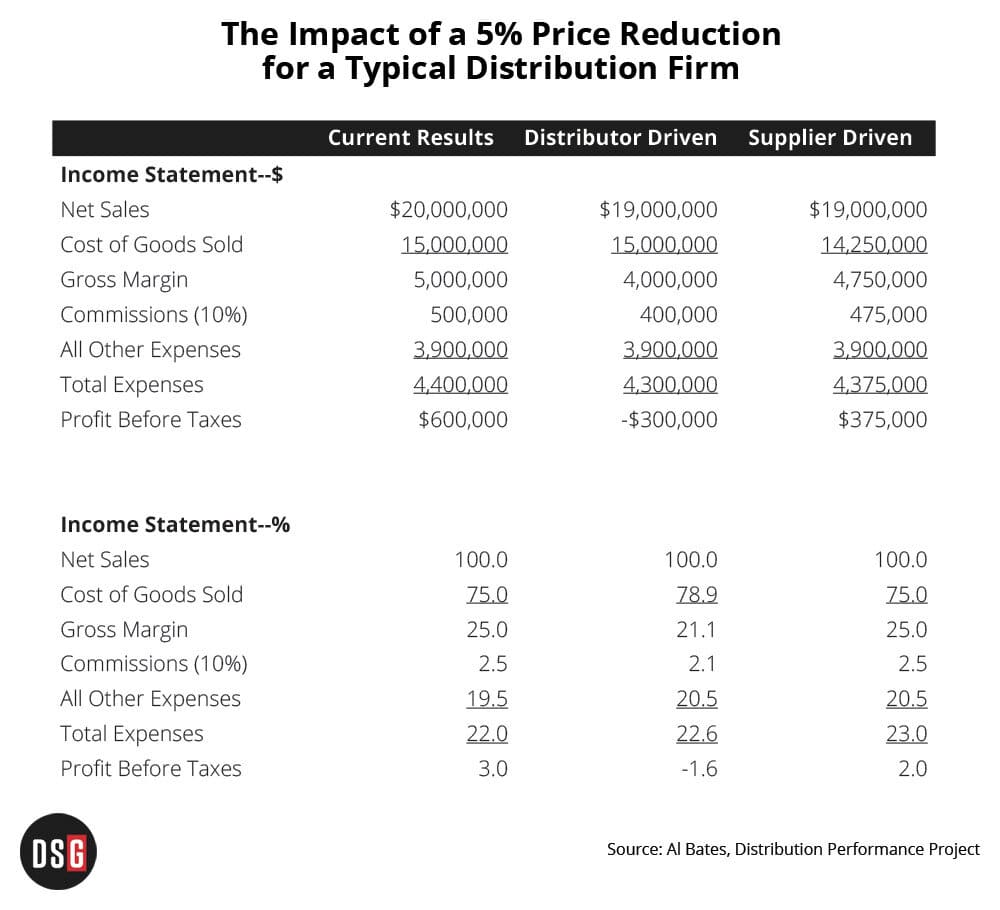

The accompanying exhibit examines the financial impact of price cutting for a representative distributor. Please note that the impact of price cutting shown in the exhibit applies to all distributors, regardless of their income statement results.

As can be seen in the first column of numbers, this illustrative firm currently generates $20 million in sales, operates on a gross margin of 25% of sales and produces a bottom line profit of 3.0% of sales or $600,000.

In looking at changes in pricing, up or down, it is necessary to break out commissions that will change automatically as pricing changes. In this example, commissions are 10% of gross margin dollars.

The last two columns of numbers in the exhibit present the potential results from price cutting under two different scenarios. The first, labeled Distributor-Driven is where the firm reduces prices unilaterally. The second, labeled Supplier-Driven is associated with passing along short-term supplier price cuts. In both cases the price reduction is 5%.

The distributor-driven price reductions are most likely the result of poor control over salesforce pricing activities. To illustrate the economic impact of distributor-driven price reductions, the price cut in the exhibit is for the entire firm. The results would be the same for a single transaction.

Revenue falls by 5% because the price cut is associated with sales that would have been made anyway. Cost of goods remains unchanged and gross margin dollars fall by the same $1 million as did sales.

Commissions remain 10% of sales. This leads to the incorrect philosophy that if the sales force cuts price, it has no real profit impact. In short, the sales force is only hurting itself. In point of fact, some salespeople may well feel that they are taking a commission hit to help the company generate a higher profit.

Alas, profit doesn’t just decline, it is decimated.

In this case, the $600,000 profit converts to a $300,000 loss. As noted earlier, every distributor will feel the same impact on profit. That is regardless of their margin and expense structure.

The final column reflects what might typically happen if a supplier offers the chance to buy more effectively in the short term. Such situations often happen near the end of the year when suppliers are anxious to hit sales target for the year. To avoid excessive inventory buildup and build share, distributors frequently pass the price cuts along.

Here is the impact of supplier-driven price cutting:

- Both sales and cost of goods fall by 5% in this situation.

- Commissions also are reduced by 5%, but other expenses remain constant.

- The net result is that profit falls to $375,000.

Clearly, this is not nearly as destructive as distributor-driven price cutting. However, the opportunity to build additional gross margin and higher profit by not lowering outbound prices has been lost.

Margin Maintenance Strategies

Avoid price cutting through education, change commission rates and strengthen price control policies. If such approaches can’t be fully implemented, two major opportunities remain.

Targeted Price Cutting: For most firms, relatively few items in the assortment are exceptionally price sensitive. The firm absolutely must be price competitive on these, even if competitors are making irrational pricing decisions. Furthermore, the firm must communicate how price competitive it is. It is not enough to cut prices here; the cut must be broadcast to maintain a positive competitive position.

As a general rule, the items that deliver the top 60% of sales volume are the genuinely price-sensitive SKUs. That means that if all of the SKUs are arrayed in order from highest to lowest dollar sales, the SKUs at the top of the list—probably 10% of the SKUs—provide 60% of sales.

It is tempting to cut prices beyond this point. In fact, there may be selected items beyond the top 10% of the SKUs that need to have price cuts, but there are probably few of them. The essential marketing point remains. If the firm must cut on highly price-sensitive SKUs it should brag about it so customers are aware the cuts have been made.

Margin Build Backs: At the other end of the product spectrum, a lot of SKUs are not price sensitive at all. In addition, during slower sales periods, these are products where competition may have reduced inventory and may not have the items in stock. These are the items on which prices can actually be adjusted upward — even during a recession — to build back gross margin sacrificed in the targeted price cutting.

Probably somewhere around half of the SKUs may qualify as margin build-back candidates. Unfortunately, they only generate something like 5% of total sales, so the increase in price needs to be significant.

However, significant is attainable. On these items, the value-add that the firm provides is availability. It is not a minor value-add; it is major. It should be a focal point of the selling effort.

Price pressures are never going to go way. However, with proper control, margins can be maintained even in price-sensitive situations.

Dr. Albert Bates is Principal of the Distribution Performance Project, a research and education entity focusing on distribution. He makes about 100 presentations each year on topics such as Improving the Bottom Line, Doing More with Less and Pricing for Profit. He also heads the firm’s investigation into profitability research for over 50 different trade associations. He has published widely in both the professional and trade press, including in the Harvard Business Review and the California Management Review. He has also authored eight books on financial planning for businesses.