“Sales solves all problems!”

While nobody truly believes that in its entirety, it certainly drives thinking throughout distribution. To use another cliché, “Nothing happens until somebody sells something.”

Note that both homilies are positive regarding sales growth.

When asked to recite a negative homily regarding sales growth, almost everybody draws a blank.

Some level of sales growth is essential in every industry, including distribution. However, empirical evidence suggests that the push for rapid sales growth almost never increases profit. Often it leads to serious financial strains. An examination of profit results in distribution over the past 20 years suggests that it may actually be possible to have “too much of a good thing.”

This article will examine the impact of sales growth on distribution firms from three perspectives:

- The interaction between sales growth and expense growth

- The methods to make sales growth profit positive rather than profit negative

- The practical limit to sales growth

Sales Growth and Expense Growth

The inherent “problem” with sales growth is that, historically, it has not improved profit. Simply put, over time every 5% increase in sales eventually resulted in a 5% increase in expenses. Consequently, in far too many cases, firms simply became a larger version of what they were before the sales increase.

As outlandish as that statement may seem, it is supported by volumes of empirical evidence. In most distribution industries, there is a benchmarking survey that tracks sales, gross margin and expenses on an annual basis. A review of those surveys reveals that expenses and profit before taxes are about the same percentage of sales that they were 10, or even 20 years ago. Again, firms have gotten larger, but not more profitable.

The financial need in distribution is to generate a level of sales growth that drives expenses down as a percentage of sales. This balancing of sales and expenses is what is commonly referred to as a real sales gain. Simply put, a real sales gain means that sales grow faster than expenses.

Surprisingly, it doesn’t make a lot of difference how fast sales actually grow — 5%, 10% or 15%. The key is that whatever growth rate is achieved, it needs to be larger than the growth in operating expenses.

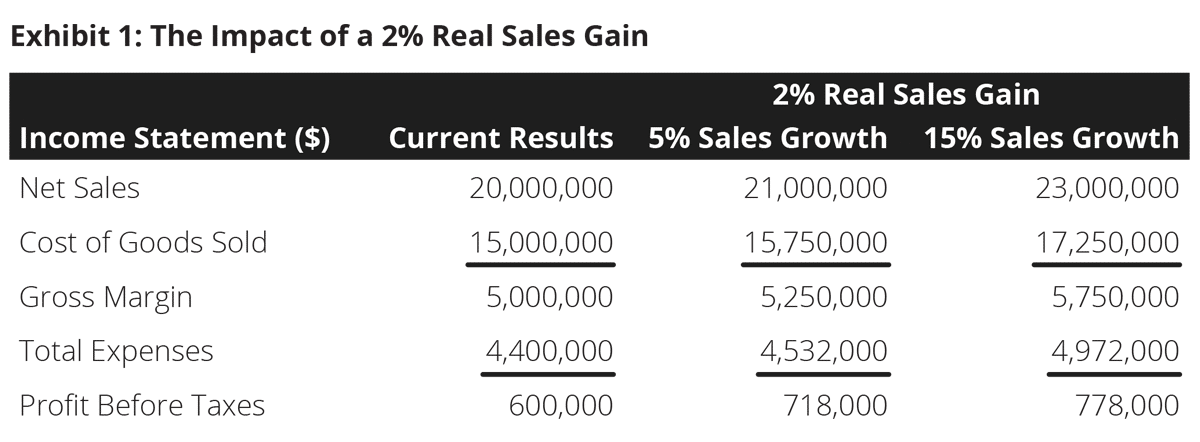

This is illustrated in Exhibit 1, which considers the current profit position of an illustrative distributor. This firm starts with sales volume of $20 million, a gross margin of 25%, expenses of 22% and a bottom line of 3%. This is close to the long-term profit performance of the overwhelming majority of distributors.

Assume that somehow (that somehow will be discussed later), the firm was able to produce a 2% real sales gain. That means sales grew exactly 2% faster than expenses. Assume further that the real sales gain was produced under two very different sales growth rates — 5% or 15%.

In the slow-growth model (5%) sales and gross margin both increased by 5% while expenses only increased by 3%. This produced a 2% real sales gain. The result is that profit increases from $600,000 to $718,000. That is an increase of $118,000 or 19.7%. (Finance guys like to be precise.)

The fast-growth model did better, of course. Sales and gross margin were up by 15%, while expenses only increased by 13% to produce the same 2% real sales gain. Profit, however, rose to $778,000, an increase of 129.7%. Higher sales growth does produce somewhat higher profits.

There are only two small flies in the fast-growth ointment:

- ease of accomplishment

- the consequences of being wrong

Both are worth a closer look.

Ease of Accomplishment revolves around the fact that 5% sales growth is not an outrageous goal. It is not automatic, but in mature markets it is attainable and realistic growth. Not easy, but realistic.

In sharp contrast, 15% sales growth in a non-inflationary environment is a real push. It is well beyond what most distributors can accomplish absent some extraordinary occurrence, such as a competitor closing down. This does not mean that 15% is outrageous; it just means there had better be a precise plan for its attainment.

Consequences of Being Wrong simply means that planning sales a year out is not a task for the faint of heart. If the 15% sales growth assumption proves true, all is well. If not, things go awry quickly.

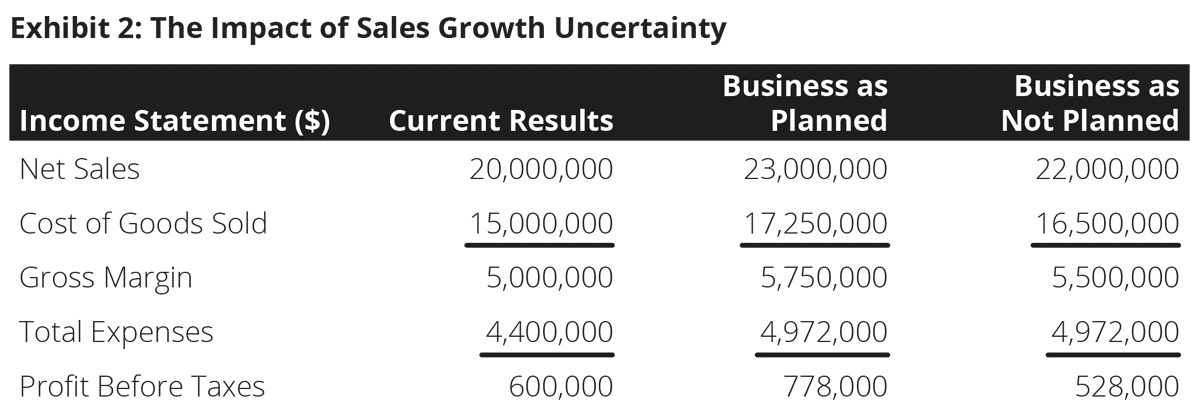

This is demonstrated in Exhibit 2. The middle column is simply a duplicate of the 15% sales growth model in Exhibit 1. Expenses only increase by 13% and profit explodes.

The last column looks at the same planned expense increase of 13%, but with sales actually increasing by only 10%. Without hyperinflation, 10% sales growth is still a strong number. It might even be the envy of the industry.

Alas, the sales growth was achieved with a decline in profit. To reiterate, it is not the level of sales growth that drives profit. It is the relationship between sales growth and expense growth. To finally bring up a negative homily from years gone by:

“Sales is vanity; profit is sanity.”

The combination of Ease of Accomplishment and The Consequences of Being Wrong should cause firms to at least consider the idea of smaller increases in sales that have a higher probability of achievement. In the real world, though, the idea of slow sales growth does not motivate anybody in the organization. Slow growth is for wimps.

As a compromise, firms should consider having two distinct sales forecasts. Assuming they can be kept straight and separate, they could motivate and ensure profit at the same time.

Firms could set their sights on rapid growth through a Marketing Sales Forecast. This serves as motivation for the sales force. After all, “15% growth is lying on the ground just waiting to be picked up.”

For financial purposes, that sales growth rate could be reduced by about one-third to produce a Financial Sales Forecast. Expense planning could then be based on the Financial Sales Forecast to produce a real sales gain. If the higher sales goal is reached, profit explodes. If only the lower sales forecast comes true, profit continues to increase as a percentage of sales.

Ensuring That Sales Growth is Profitable

In thinking of sales growth, particularly rapid sales growth, there is a natural tendency to focus on what can be called External Sales. Such sales come from areas that do not presently exist. It is a composite of new branches, new customers, additional sales personnel and possibly new products.

External Sales are essential for the long-term success of the firm. However, they are virtually all expense-first, sales-second concepts. They build the base for the future but make a real sales gain challenging. They need to be seriously supplemented by Internal Sales Programs. Seriously supplemented means a concerted ongoing effort to maximize sales through this vehicle.

There are at least three attack points in the Internal Sales Program. Two of them are well known and will only be mentioned here. The third is not well understood and will be reviewed in some detail.

Transaction Enhancement involves putting a few more items on every order. The increase in sales is achievable with only a modest increase in cost as it is the same number of orders to existing customers. This remains an attractive opportunity but has not been widely implemented given the need for sophisticated transaction analysis to measure success or failure.

Customer Churn looks at the number of customers that are lost over time. Often the loss of a customer is viewed as a surprise. However, departing customers leave hints all along the journey to another supplier. These include fewer orders, smaller orders, or more active price negotiation. Solving the customer churn problem is an ideal opportunity for AI systems to monitor performance and develop actions to avoid the churn to the extent possible.

Churn has two negative parameters. First, of course, is the loss of sales from departing customers. The second is the previously mentioned cost of finding potential new customers and enticing them to buy.

Sales Force Performance is an overlooked area of sales-to-expense improvement. A major reason that it is overlooked is that the sales force usually is compensated heavily on commissions. The feeling is that if a rep isn’t quite as productive as possible, the decline in commissions will offset the sale loss. The rep is penalized rather than the firm.

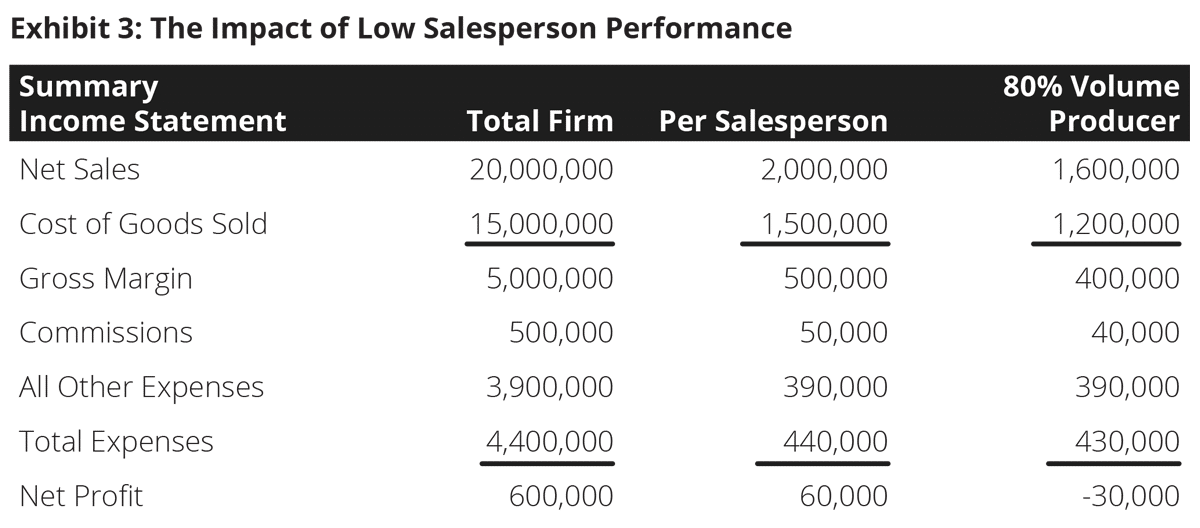

To understand the impact of lower sales performance, assume that the illustrative company being analyzed has 10 salespeople and that they receive a commission of 10% of the gross margin generated. Also assume that every territory has equal potential. This is never the situation in any business, but it allows for easy calculations in the exhibit. With $20 million in total sales and 10 reps, each rep produces $2 million in sales and $60,000 in profit.

Exhibit 3 looks at a situation where one of the reps produces only 80% of the volume potential in the territory. This is not a terrible performance. Since accurately calculating the potential per territory is difficult, it might be completely overlooked. In a job market where finding potential new reps is difficult, it might be not only overlooked, but completely ignored.

With lower sales, the cost of goods and gross margin fell, as well. Commission also falls. There has been some real expense relief to offset the lower sales and margin.

The problem is that All Other Expenses do not budge. Because every territory has been made equal in potential, every territory has to cover its share of overhead expenses. The result is that profit, in comparison to potential, not only falls, but goes negative.

If the other reps are performing properly, the one-rep problem seems inconsequential.

So, what can the firm do about it?

The most obvious something is more training. However, research suggests that poor-performing sales reps remain poor-performing, even after extensive training. Ultimately, the unfortunate solution is replacement.

Even if firms know they have reps that are not producing to their potential, they tend to avoid replacing them. This is because there is a large and well-known cost of finding a replacement rep.

Replacement costs are a one-time cost, however. The cost of having underperforming sales reps is an on-going cost. It is there every year.

The Practical Limit to Sales Growth

It seems counterintuitive, but sales growth actually can be excessive. That is, rapid sales growth will cause the firm to outrun its financial capacity to fund that growth.

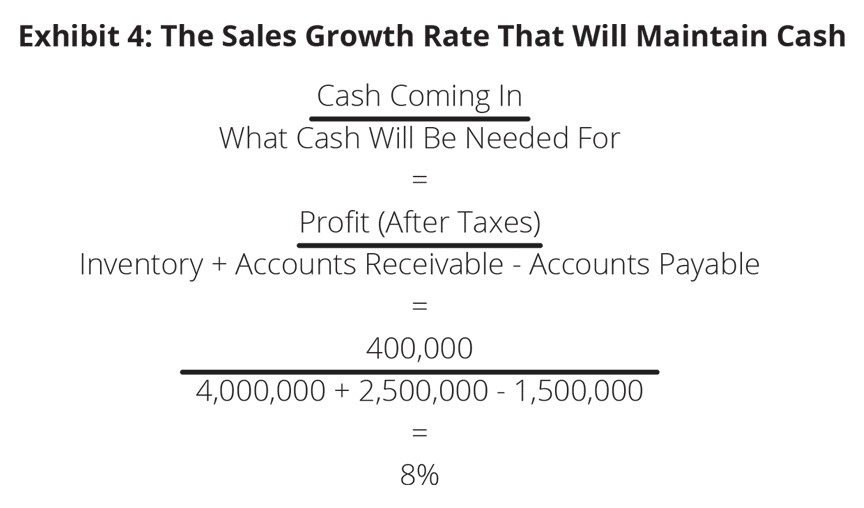

Unfortunately, figuring out exactly how fast a firm can grow requires dealing with some rather ugly ratios. One is the Growth Potential Index (GPI) which estimates how fast a firm can grow without using up any of its cash. That is, it ends the year with about the same amount of cash as it had at the start of the year.

The ratio compares how much cash is coming into the business (defined as after-tax profit) in relationship to the three key working capital items — inventory, accounts receivable and accounts payable. Both inventory and accounts receivable will increase with sales over time, eating up cash. At the same time accounts payable will also increase. The GPI tries to measure if the cash coming in will cover the increase in investment.

For the illustrative firm with $20 million in sales, a reasonable tax rate is one-third (higher in many states, lower in many others). This means that after-tax profits are $400,000. Assuming that all the money is invested back in the business (often true, sometimes not), this is what is available to fund the increase in working capital.

For a firm with $20 million in sales, it is reasonable to expect that accounts receivable would be around $2.5 million, inventory $4 million and accounts payable $1.5 million. These would vary from industry to industry but are serviceable estimates.

Given this, the firm’s GPI is:

This formula assumes that as the business increases, profits will increase in direct proportion. That is, a 10% increase in sales will result in a 10% increase in profits, as well. Again, this is what has happened in distribution over time.

If firms were able to have profits increase faster than sales, then the ability to grow would increase, as well. For extremely profitable firms, the CPI is not even a real barrier. For most firms, it must be considered.

Increased sales will have an impact on two aspects of the firm’s business — its income statement and its balance sheet. The next two exhibits look at both situations.

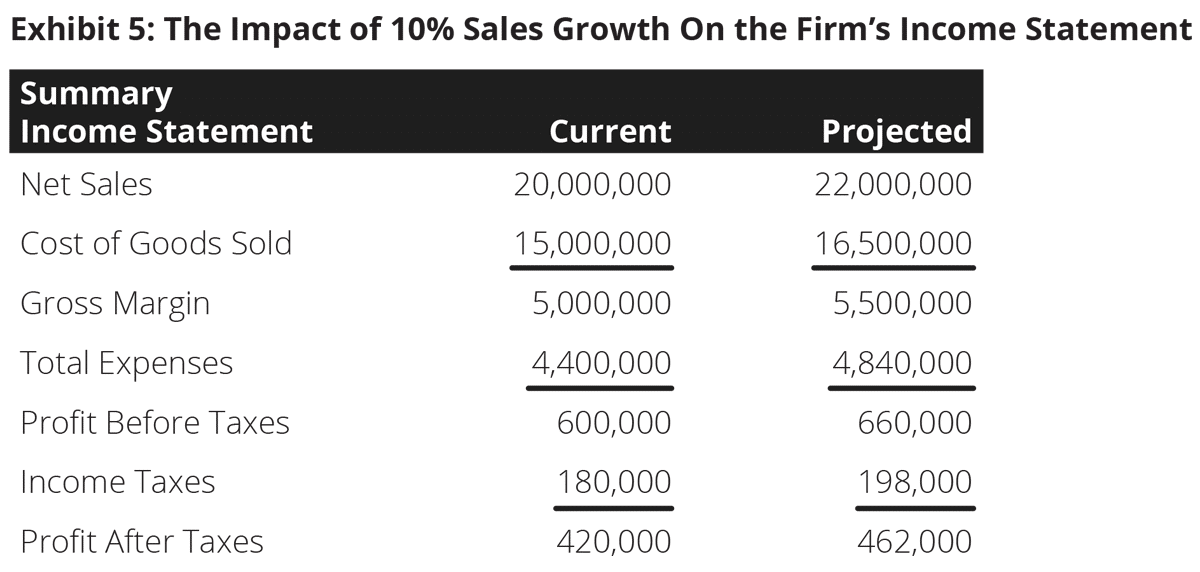

Exhibit 5 takes the same firm that had an 8% GPI and elects to grow at 10%. The exhibit looks at the income statement side of the business. All the figures in the Projected column have increased by the same 10%. Again, this is what tends to happen in the long term.

As can be seen, the firm’s profit after taxes increases from $420,000 to $462,000. The firm is increasing sales and profits at a rate in excess of its 8% GPI. From an income statement perspective, this is solid performance.

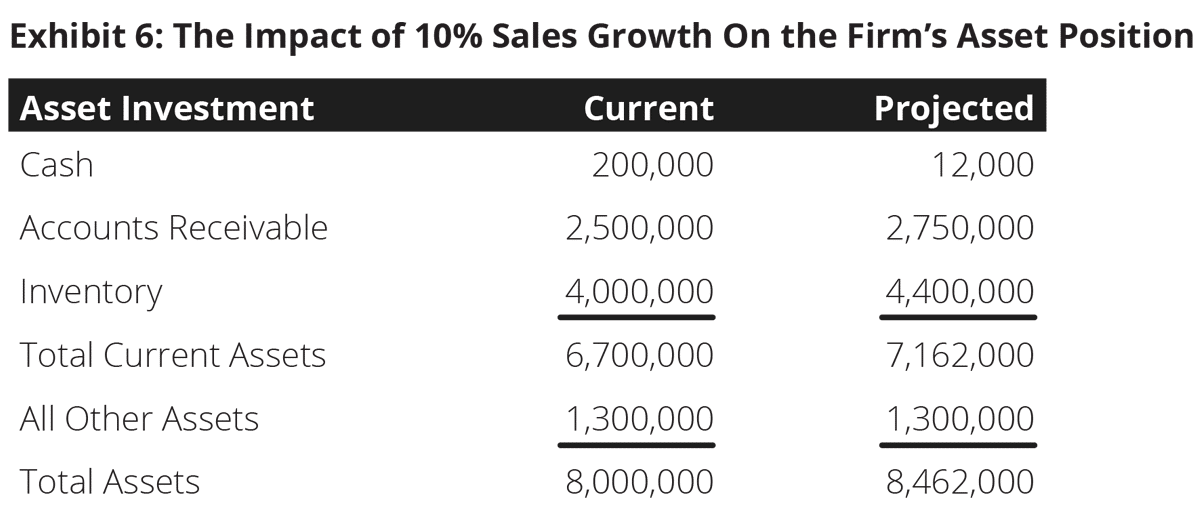

Exhibit 6 looks at the investment implication of the sales growth. Starting at the bottom, it is assumed that the entire after-tax profit of $462,000 is reinvested back into the business. Total assets are increased by that amount. For family-run businesses, this might not reflect reality. Even for large firms, dividends could reduce the reinvestment amount.

The second line from the bottom assumes that All Other Assets category (fixed assets and any other current assets) remains constant. That means that the total of Working Capital Assets also increases by $462,000.

After that, both accounts receivable and inventory increase by the same 10%. With regard to accounts receivable, this is an automatic result. Unless the firm changes its terms of sales, sales increases drive higher accounts receivable in real time.

Inventory is another issue. The increase may not come automatically, but over time inventory will rise along with sales. To illustrate how sales impacts the firm’s cash position in the longer term, it is reasonable to view the impact as immediate.

The punch line is that after financing the increase in inventory and accounts receivable, cash falls dramatically. It is inevitable.

All is not lost, of course. The firm can use its line of credit to replenish cash. It can also engage in long-term borrowing. In both cases, what the firms gains in maintaining cash it loses in terms of profit to generate future cash.

Suggestions For Action

The author is not crazy enough to suggest firms limit their sales objectives. Instead, three suggestions seem appropriate:

Plan Around the GPI (or other ratio) — It is essential to know how fast the firm can grow without outpacing its financial capabilities. If the growth goal is more than the GPI, specific actions, such as secured lines of credit, must be in place. Plans to drive higher profits and increase the GPI are always welcome.

Control Expenses, Especially Payroll in Relation to Sales Growth — Use a conservative estimate for sales growth and plan expenses to grow at least slightly slower than sales. Because payroll is typically around two-thirds of total expenses, this must be a central part of the plan.

Focus on Actions That Drive Sales Faster Than Expenses — Identify the areas where the firm can make changes in order economics, customer churn and salesforce productivity.

Ideally, implementing these strategies will have tangible results. The likelihood that large numbers of firms will take this to heart is minimal. For individual firms, though, the potential is there.

Dr. Albert Bates is Principal of the Distribution Performance Project, a research and education entity focusing on distribution. He makes about 100 presentations each year on topics such as Improving the Bottom Line, Doing More with Less and Pricing for Profit. He also heads the firm’s investigation into profitability research for over 50 different trade associations. He has published widely in both the professional and trade press, including in the Harvard Business Review and the California Management Review. He has also authored eight books on financial planning for businesses.

1 thought on “Sales Growth Myopia in Distribution”

Be careful with your calculations. “The results is that profit increases from $600,000 to $718,000. That is an increase of $118,000 or 119.7%. (Finance guys like to be precise.) ”

An increase of $118,000 over $600,000 is 19.67% increase in profit.