Over the past few years, distributors have enjoyed the benefits of continually rising prices. By passing along supplier price increases percent for percent to customers, firms have recorded record profits in almost every segment of distribution.

Data from financial benchmarking programs indicate that profits in 2022 were higher than they have been in more than 20 years. In fact, in some industries PBT (Profit Before Taxes as a percent of Total Sales) was twice as high as in any other year in history. Such is the power of supplier price increases passed along to customers.

As hyper-inflation has given way to more moderate rates of inflation, the increase in profits has moderated. However, the overall change in the margin and expense structure flowing from inflation remains. There is seemingly a new plateau.

Unfortunately, as Herbert Stein so wisely stated: “If something can’t go on forever, it will stop.” Not only is inflation moderating, there are some anecdotal incidents that suggest that some supplier prices are falling.

There is no need to panic about deflation at this point, even though China appears to be in such a brutal position. A more realistic assessment is that distributors are facing sporadic price reversals. Whether they remain sporadic or burst into deflation is an issue for economists. What managers need to know is the impact that falling prices, sporadic or otherwise, have on financial performance.

This article examines supplier price reductions from two perspectives. The first is the actual profit impact. The second is strategies for offsetting declining prices.

Profit Impact of Declining Prices

In simplest terms, the impact of declining prices is the mirror image of the price increases of the last few years. Namely, they will decimate profits if the price reductions move from sporadic to universal. That is, if there is full-fledged deflation.

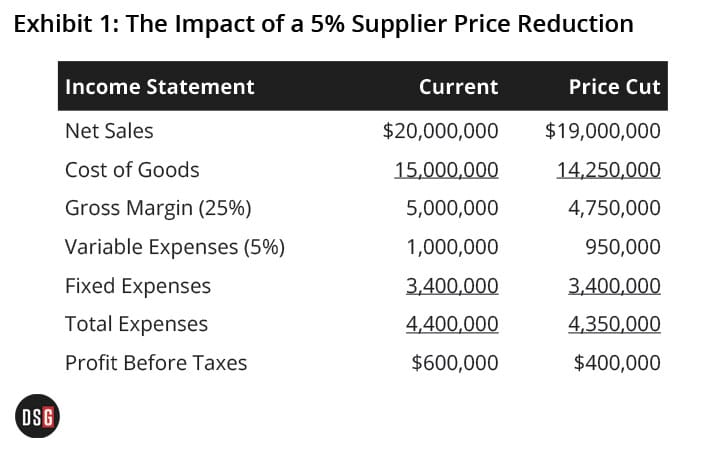

Exhibit 1 examines the financial results for an illustrative distributor facing a 5% price reduction across the board. The exhibit uses numbers that are typical for a wide range of distribution firms.

The firm with, $20 million in sales, operates on a gross margin of 25% and produces a bottom-line profit of 3% of sales. It is important to note that for firms falling outside of this range everything that will be said about the illustrative firm will be true of all firms.

The one item in the exhibit that is not self-evident is the breakout of fixed and variable expenses. Any time there is a sales change, both expense groups need to be addressed. Fixed expenses are essentially overhead expenses that do not change as sales rise or fall unless the sales change is dramatic. In sharp contrast, variable expenses rise and fall with sales. They include sales commissions, bad debts, interest on accounts receivable and inventory and a few other minor items. They are assumed to be 5% of sales.

The exhibit examines a 5% supplier price reduction on all items. This across-the-board assumption is necessary to conduct any meaningful analysis. The results shown in the exhibit would be true for an individual supplier or product category.

The more important assumption is that because of the high level of information regarding the price cut and competitive pressures, the firm feels forced to lower its prices by the same 5.0%.

As can be seen, sales and gross margin both decline by the same 5%. However, profit before taxes declines by 33.3%. This is the reverse of what has been happening to profit during the era of constant price increases.

Clearly, it does not take much in the way of deflation to cause some serious profit issues. The objective for distributors is to not have to match the 5% decline in its entirety. Towards that goal, it is useful to examine how much of a moderation to the outbound price reduction would be necessary to hold profits where they are — $600,000.

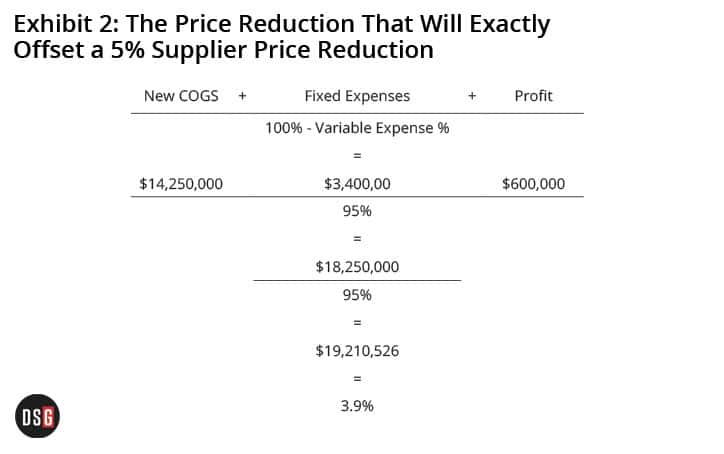

A variation of the breakeven formula for the firm provides an answer. This formula is the same one that was used in a previous article published by the Distribution Strategy Group involving price increases: Practical Post-Pandemic Pricing for Profit. In that report, prices were going up; in this case they are going down.

As can be seen, if the firm could only reduce prices by 3.9% outbound, it could maintain the profit of $600,000 in face of a 5% supplier price reduction. The open issue is how to ensure that the price reduction outbound is less than the one inbound.

Strategies for Offsetting Price Declines

While the financial ramifications between price increases and price decreases are mirror images, the strategies for maintaining profit are largely the same old same old. The only difference is a minor adjustment in emphasis.

The three most important strategies are:

- enhancing order economics

- proper pricing of the long tail of the product line

- adjusting inventory positions

Order Economics—As prices fall, dollar volume falls in conjunction with the price decline. This means that most expense categories, expressed as a percent of sales, will increase automatically. Some of these are minor issues that can be managed. Payroll costs are neither minor nor manageable.

Payroll costs (fully loaded with social costs) represent about two-thirds of total expenses for virtually every distributor in every line of trade. At present, the upward push on labor costs has moderated slightly. Having said that, there is no way that labor costs can be pushed down simply because prices are also being pushed down.

To hold the line on labor costs, firms will need to focus intently on order economics. That simply means looking at the composition of orders — the number of lines per order and the average line extension. Both of these are important, but one of these is already tied negatively to declining prices.

As prices fall, the average line extension falls in unison. Some relief to this issue will be provided in the next section on pricing individual items. At best these suggestions will provide only minor help with the line extension issue.

Most of the emphasis will have to be on increasing the quantity purchased on each line extension. Ongoing efforts to encourage firms to purchase less frequently have value here, but involve a slow, time-consuming process. It is not “abandon hope all ye who enter here.” It is, though, clearly a second-tier goal.

The primary emphasis must be on putting more lines on every order. The impact of such an effort is to raise sales modestly while having payroll costs rise imperceptibly. There are more order lines to be processed, but with the same number of orders and deliveries going through the system.

Increasing the number of lines per order automatically suggests training, motivating, compensating, and controlling sales force performance. Over time, everybody, including the sales force falls into bad habits. The lack of add-on selling is a prime example of this. Constant attention is needed. To be blunt, attention without specific information on order economics is useless. More information on salesforce performance with regard to order economics is essential.

What is sometimes overlooked is that the firm has two other levers for increasing lines per order. The first is to make sure that customers are fully aware of the extent to which the firm can provide one-stop shopping. The old customer question of “when did you put that in the product line” with an answer of “back in 2007” is still true in distribution. Providing one-stop shopping is giving most customers what they really want.

The final way to enhance lines per order is to make sure the service level is maintained at a proper level. Alas, there is no such thing as free lunch and some negative results of this in a market with declining prices will be discussed shortly.

Pricing Slower-Selling Items—Much has been made in distribution about the need to generate higher margins on slower-selling items, particularly the ones that are only purchased when they are absolutely needed. Since such items may be purchased infrequently and are usually of small value, margin enhancement opportunities abound.

If prices are falling, this idea takes on added importance. In Exhibit 2, it was indicated that if supplier prices fell by 5%, the firm could maintain its dollar profit by only allowing prices outbound to decline by 3.9%. As with most financial models, the exhibit is big on what to do and light on how to do it.

Clearly, outbound prices on fast-selling items, about 60% of the sales mix, are going to fall right along with the supplier price increases. These are the items where customers build price perceptions. Firms that have high prices on fast sellers are perceived as high on the entire product line.

At a minimum the firm should try to hold the line on the C and D items, collectively about 2% of sales. There may be a few exceptions that required downward price adjustments in this group of products. They are what the previous sentence suggested—a few exceptions.

For D items, it is worth a try to actually raise prices outbound. This may seem counter-intuitive. However, it is worth nothing once again that these items are bought infrequently, often in an emergency situation, and are low-value items. The value added is not the price level, it is the availability. Prices should be adjusted accordingly.

Inventory Levels—Ideally, space limitations for this article would mean that this topic can be avoided by the author. Strategic realities demand that it be discussed.

When prices are going up rapidly, the clear implication is to load up on inventory to the extent that the firm’s cash position allows. As prices rise, the value of inventory on hand increases, generating what is commonly called inside margin.

If prices are falling, even for a few items, inside margin becomes negative. The profit-maximizing approach is to carry as little inventory as possible. This proposition runs head long into the need to maintain service levels that was mentioned at least twice in previous sections. Inventory-reduction programs inevitably become sales-reduction programs.

Firms need to work closely with key suppliers to ensure that the supply chain allows the firm to continue to “be in stock all of the time” while operating on minimum inventory levels. Once again, an important word appears, in this case “key suppliers.” This is something that can only be done with concerted effort at a few supply points.

The ultimate, but alas again long-term solution, is to eliminate tertiary suppliers and consolidate inventory into few SKUs. The profit calculations of this are way beyond this discussion. The conclusion is always the same though—driving the equivalent sales through fewer suppliers results in higher service levels without higher inventory levels. Working with fewer suppliers also causes the firms to be a better customer and avoid many supply-chain challenges.

Moving Forward

The idea that prices may start to decline could simply be an aberration based upon a few anecdotal examples. At the same time, those anecdotes should not be ignored. Firms should have clear plans for those situations where prices really do fall.

Luckily, any potential price decline can be offset if firms simply focus on what they should be doing at all times—rising prices, falling prices or stagnant prices. That is to focus on what really drive profit—order economics and gross margin maintenance with proper pricing procedures.

Dr. Albert Bates is Principal of the Distribution Performance Project, a research and education entity focusing on distribution. He makes about 100 presentations each year on topics such as Improving the Bottom Line, Doing More with Less and Pricing for Profit. He also heads the firm’s investigation into profitability research for over 50 different trade associations. He has published widely in both the professional and trade press, including in the Harvard Business Review and the California Management Review. He has also authored eight books on financial planning for businesses.