The primary growth engines for wholesale distributors have been acquisition, outside sales and fee-based services. These growth methods are decades old and, based on our work and research, offer incrementally smaller operating profits and come with a host of problems. Growth is necessary for the wholesale firm to maintain its viability.

As real GDP grows, most of the over four dozen distinct product market sectors served by B2B distributors will also grow. However, they will need to adopt a new organic-growth method, structured market targeting. Otherwise, distributors risk:

- Incrementally smaller profits as the marketplace consolidates

- Online distributors increasing their presence

- Old growth models creating operating friction that limits earnings

Problems with Existing Growth Models

Most distribution broad-market sectors are nearing a century of age. Construction sectors of plumbing, HVAC and electrical are over 100-years-old while more recent industries, inclusive of computers, peripherals and medical suppliers, are over 50-years-old. Many of these sectors have consolidated as family generations sell to super-regional or national firms. However, there remains a significant amount of regional and local branch-based companies that will sell as their industries continue to leverage costs with technology and new management methods.

Outside Sales

Outside selling has been a relied-upon model of growth since distribution’s inception during the Industrial Revolution. In recent times, customers can order, search and compare commodities online with limited to no help from outside sellers. Many of today’s leading distributors are solely online, a trend that surfaced in the B2B sector in the last 10-12 years. Of note are that these firms grew to the top of their respective vertical sectors without an outside sales effort and plethora of branches.

Many distributors still cling to outside sales as a growth model but pay dearly for the luxury. Outside selling is one of the most expensive parts of the distributor operating platform, often running 20% or more of margin dollars. Also, outside selling creates a firm where there is significant operating friction as sellers change service and product commitments outside of the standard offering. Variation in products and services are too often fomented or appeal to the comfort zone of individual sellers.

Our findings are clear: If the distribution firm has a geographic, generalist sales effort, they are most likely generating below-average operating income and have incongruous operating policies. Additionally, if pricing is sales-driven, you can almost always expect below-average margin percent.

Consolidation

Consolidation has been a growth standard in distribution for over three decades. Some firms, including Ferguson, Sonepar, Wurth and others have grown significantly through acquisition and, today, are leaders in their sectors.

Successful, long-term acquisition comes with a detailed onboarding plan. The newly acquired face significant cultural changes and operating demands as new, better and less costly processes are often part of the changes forced by the acquiring firm. These changes can run the gamut across all functions and depend on what financial and operating condition the acquired firm is in.

Our findings are that most family-owned firms, after acquisition, don’t retain family management and key officers for much more than a year. The changes forced by the larger, acquiring firm often make the jobs untenable as the demands and pace of large corporations, driven for quarterly profits, are very different from those of smaller, regional firms; especially those that have operated as a lifestyle business.

Acquisition is not only limited to national firms that, primarily, acquire regional or larger firms.

There are a class of regional/super-regional firms that acquire much smaller local companies, typically in the $10MM to $20MM, range. They often grow into the hundreds of millions of dollars. However, many of these firms run into difficulty as significant acquisitions of tribal cultures and on-the-fly operating procedures clash. The consolidated operating platforms become “gummed up” with varying experiences. At some point, expenses rise faster than revenues and operating income suffers. Many of these firms end up selling to a national entity.

Fee-based Services

Lastly, fee-based services have offered incremental growth with margins often greater than product sales for the past quarter century. The problem with fee-based services, however, is two-fold; unique services are increasingly rare, and the technology cost for service revenues often grows at a faster rate than fees. Services such as vending machines, vendor managed inventory and consultative sales services are an ante to compete. Decades ago, these services were differentiators. Today, many distributors have them. Unique, standalone services for existing products and technologies, are rare.

The growth engines of the past inclusive of outside sales, acquisition and fee-based services, while still viable, offer less contribution to operating income than in years prior. These growth efforts wear away at earnings as they create misalignment of functions. Our view is that distribution needs a new, better-aligned and better income-producing growth method.

Structured Market Targeting

Wholesale distribution has traditionally been sales-focused. In the early years of the industry’s lifecycle, selling was the best and perhaps only way to get new technologies to market. As the technologies matured, catalog houses, including Grainger¹, began to appear. The idea of Structured Market Growth follows planned marketing efforts of industrial manufacturers. The subject had its genesis in the 1980s and widespread adoption in the 1990s.

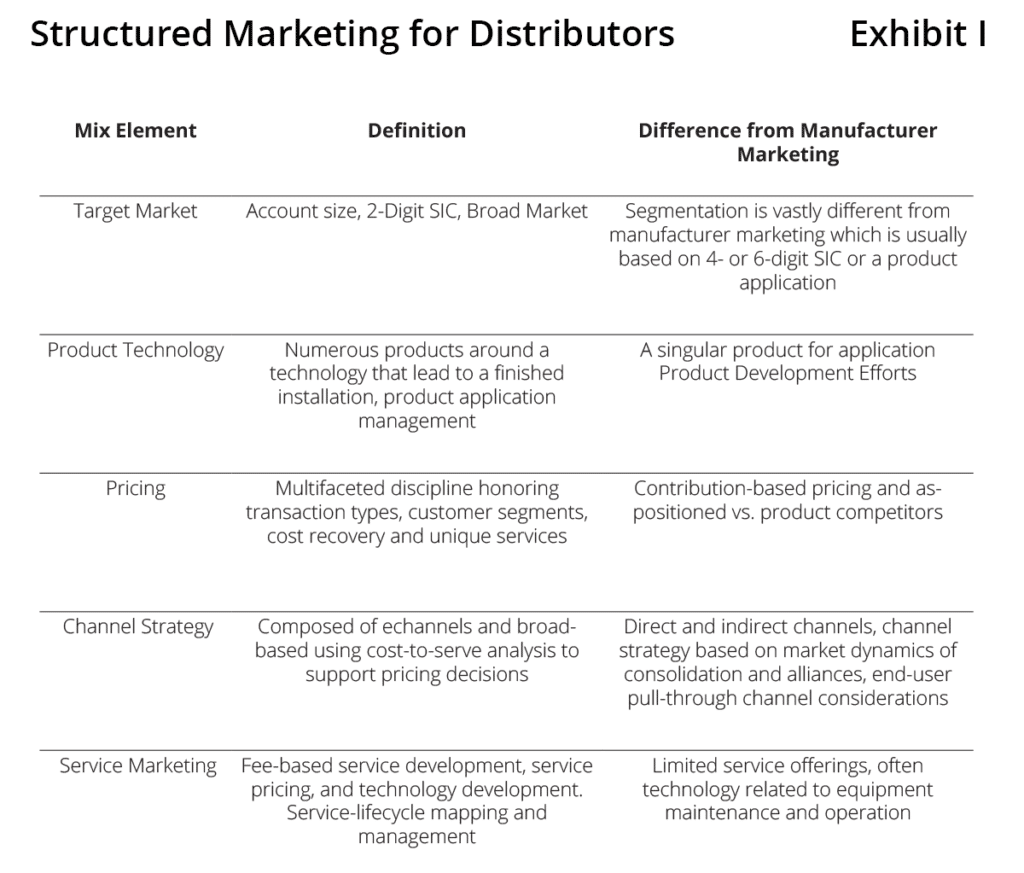

Today, the discipline is captured under the umbrella term of B2B marketing.² But structured marketing for distributors differs vastly from standard manufacturer marketing. Market definition, cost structure and application of the marketing mix are different and demand a discipline tailored to the unique demands of the distribution firm.

Exhibit I gives an overview of the major components of structured marketing and how these differ between manufacturer and distributor.

In the Exhibit, we have the elements of the B2B marketing mix with the notable differences with manufacturer marketing. Some of the more notable differences include:

- Segmentation for distributors is typically broader based than those of manufacturers and includes account size, two-digit SIC code or broad-based industry.

- Product technology for distribution concerns numerous products that make a finished application vs. singular products for manufacturers.

- Distribution pricing is more complex than that of manufacturers and concerns transaction types, service pricing and cost-to-serve analyses whereas manufacturer pricing is primarily based on contribution accounting.

- Service marketing and new service development for distributors is significant and an important part of the go-to-market offering. In most manufacturers, service marketing is limited to tech efforts to support the product.

From its namesake, structured marketing starts with the marketplace and works backward to align the firm’s functions to approach and successfully penetrate a market. Few sales-driven distributors have this perspective while a growing number of the billion-dollar players have discovered and successfully applied it. The earnings history of sales-driven firms, mostly regional or super-regional entities, versus national and global firms, tells the difference.

Firms such as Grainger, Ferguson, Wurth and other billion-dollar entities have operating profit as a percentage of sales in the 7% to over 10% range. This is compared with mid-market distributors who often struggle to get similar metrics to 3% or more of sales in any given year.

The observation is often made that the billion-dollar players have better negotiating power over their supplier base and pass the savings on to the profit line. Our counter, however, is that mega-buying groups including Affiliated Distributors and IMARK, whose collective member revenues are in the billions, have significant leverage of the same vendor base; hence buy-side advantage is, largely, a non-sequitur.

A growing number of billion-dollar players have established and powerful marketing efforts while many of the mid-market players do not. Too often mid-market firms confuse marketing with marketing communications.

Many mid-market distributors question why they should invest in structured marketing as sales, acquisitions and fee-based services have supplied top-line growth. Marketing accomplishes three primary objectives for the wholesale firm:

- It targets broad groups of customers with growth potential and where the firm has successful past growth.

- It creates alignment across functions with a Structured Market approach. It helps the firm avoid friction arising from competing functional silos that creates operating friction and reduces income.

- Structured marketing growth is organic and hence more durable than sales-driven or acquisitive growth. It marshals functions into an aligned approach to growth. The result, if done correctly, is improved operating profits.

Personal selling and fee-based services are almost always account-based. The larger the account, the more the seller, rewarded on margin dollars, will customize the service and product offerings. This creates complexity and, repeated numerous times, drags down earnings as the firm reels from an operating platform that, if traced out, resembles a bowl of spaghetti.

Our work in activity costing for over three decades repeatedly finds distributors serve large customers with customized services and non-standard products often at an operating loss. They rob activity-positive customers of service capacity to service the needs of the large-revenue, activity-negative account. The dysfunction is catalyzed by rewarding outside sellers on margin dollars without any counterbalance for cost to serve.

Unless the mid-market wholesale firm seeks better service and strategic alignment for their growth efforts, they will continue to suffer earnings that pale in comparison to the billion-dollar entities. The need for alignment, reduction in functional silos and growth planning is generally not found in the mid-market distributors across North America.

Many of these firms go to market as they always have without a central plan, relying on sales growth or acquisition to move the top line forward. In these firms, most often, sales growth does not grow faster than inflation and new account growth, of any significance, is due to a competitor-key customer relationships going awry.

Mid-market wholesalers, if they are to remain independent, grow organically and improve income streams on par with the billion-dollar competitors, need to change. They will need to ease reliance on personal selling, acquisition and fee-based services toward a more balanced growth effort.

Structured Market Growth Model

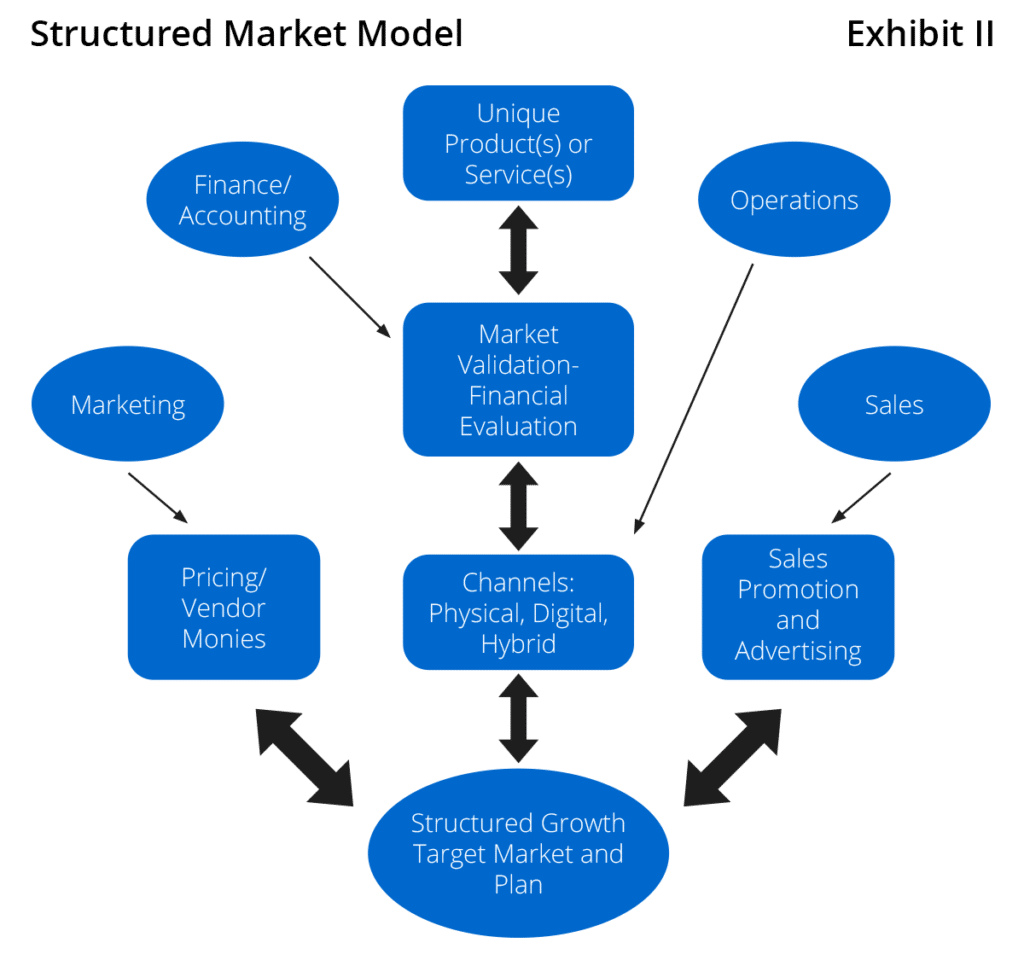

Structured market growth rests on two fundamental elements:

- The identification of a unique value stream

- A plan to align corporate functions to capture the market opportunity. Without these elements, there are limited reasons to pursue structured growth. The structured growth model can be seen in Exhibit 2.

In the exhibit, the connecting arrows flow both ways. Structured marketing starts at the market opportunity and works backward into the core elements of the plan. Included in the structured market approach are:

- Identification and financial pro-forma of market opportunity,

- Integrating the marketing mix including pricing, channel strategy and sales promotion,

- Supporting efforts worked into the plan from finance, marketing, operations and sales.

These three elements combine to develop a plan before any substantial financial investment is made to increase the market opportunity. Done well, structured growth eliminates much of the friction and dysfunction caused by personal selling and acquisitive growth.

A common challenge in structured market growth is the identification of unique value streams. Most wholesalers have difficulty with this portion of structured growth planning. Unique value streams have several identifiers including:

- They are unique to the company and are seldom copied by competitors; they may be early in their lifecycle.

- They usually involve a unique service or services wrapped around a new or newer technology product or product application.

- They show a faster rate of growth than aggregated sales during the same accounting period.

In our planning sessions, many distributors bring forward unique value streams, only to have them fail the previous bullet points. Often, distributors may not know their unique value streams and need to further mine sales data to find them. While structured planning can help all top-line sales activity, it is best used for unique value streams as it concentrates effort and reduces bottlenecks across functions.

Decisions and planning on pricing, channels and sales promotion, as well as functional supports are noted in the model but beyond the scope of this article. Experienced marketers and upper-level managers need to be involved in the development of the go-to-market plan. Our experience is that many distributors don’t have the necessary know-how to develop a structured market plan and implement the changes required to secure growth. An outside resource can help this process and, once it is successfully completed, the experience can be repeated internally by the wholesaler.

Future Notes

Distributors, especially mid-market firms, need a new method of growth other than acquisition or account growth through outside sales. These growth methods are decades old and cause considerable operating friction through specialized process and product demands. A growing number of billion-dollar firms use a structured growth approach while many mid-market firms are oblivious to its need. Today, the billion-dollar firms outperform their mid-market peers, on pretax margins, as a percentage of sales, by a 2X to 3X multiple.

We encourage all distributors to review the opportunity for structured, planned, market growth. A well-written plan around a unique value proposition can lead to organic growth for years to come.

¹Grainger began in 1927 but this is some 50 years or more after the start of industrial distribution that sprang out of manufacturing that supplied the Union cause in the American Civil War (1861-1865).

²Industrial Marketing for manufacturers, today named B2B Marketing, and structured market growth began in the 1980’s and 1990’s. The concept and practice formed in leading U.S. graduate schools including Northwestern University, Wake Forest University, and Case Western. Initial professors who studied and encouraged the discipline included: Philip Kotler, James Makens, Jim Anderson, Jim Narus and Jim Hlavacek.

Scott Benfield is a consultant for B2B Manufacturers and Distributors. He is the author of six books and numerous research projects on B2B channels. He can be reached at benfield.scott@aol.com or (630) 640-5605.