How Master Distributors Add Value

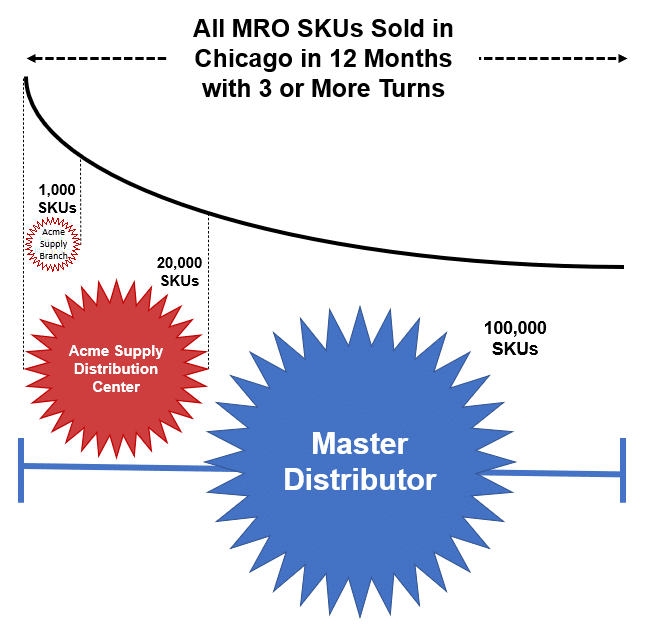

For decades, distributors have decided what SKUs to keep in stock based on sales frequency. While there are various iterations, the most basic (and arguably the most common) approach is to set a cut-off line for sales frequency and stock SKUs above the line but not those below it.

For example:

- If a SKU sells three times / year = keep in stock

- If a SKU sells less than three times / year = do not stock

The number of SKUs that earn stocking status is directly related to the size of the market a given location serves. A branch servicing a small part of a city will stock less than a distribution center serving a large metropolitan area.

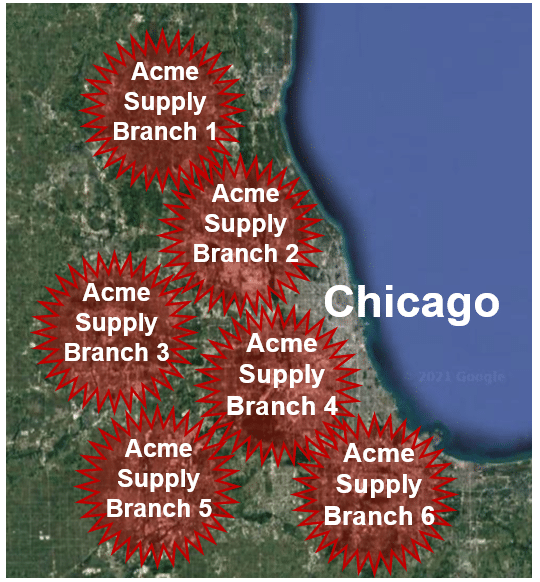

Using Chicagoland to illustrate this concept, consider an MRO distributor called Acme Supply** with six branches in the area. Each branch services the customers immediately surrounding it, as represented by the red circles.

There may be some overlap between the branches and the company may connect the information systems of all the locations so they can share inventory records. For the most part, however, the on-hand inventory for each location will reflect that branch’s historical demand: SKUs that sold three times in the past 12 months within that branch’s service area will be in stock. SKUs selling less frequently than that will not be stocked.

Because Acme’s customers will often call a branch and ask for items not stocked there, the company will rely on four capabilities to provide a broader assortment of products:

- Acme may build a distribution center to serve all of Chicagoland.

- Acme employees may source products from other distributors.

- Acme may contact its manufacturers and ask them to ship direct to customers.

- Acme branches may rely on a “master distributor” to source items not carried by the company. We will define “master distributor” shortly.

An Acme distribution center can justify carrying a broader range of SKUs than a single branch simply because the DC supports many more customers – all the company’s Chicagoland accounts, in this example. A branch may have 1,000 SKUs that sell three times a year and are thus stocked while a DC may have 20,000 SKUs that sell three times a year because it is serving all customers in the metropolitan area.

However, if the customer is asking for an item not stocked by the DC (for example, a brand Acme doesn’t carry), a customer service rep may source the product from a competitor, ask a supplier to ship it directly or order it from a master distributor. For our purposes, we will define a “master distributor” as a wholesaler that only sells to other wholesalers and, in some cases, to retailers. Master distributors do not sell to end customers. Distributors that do sell to end customers – like Acme in our example – are often called, “merchant wholesalers.”

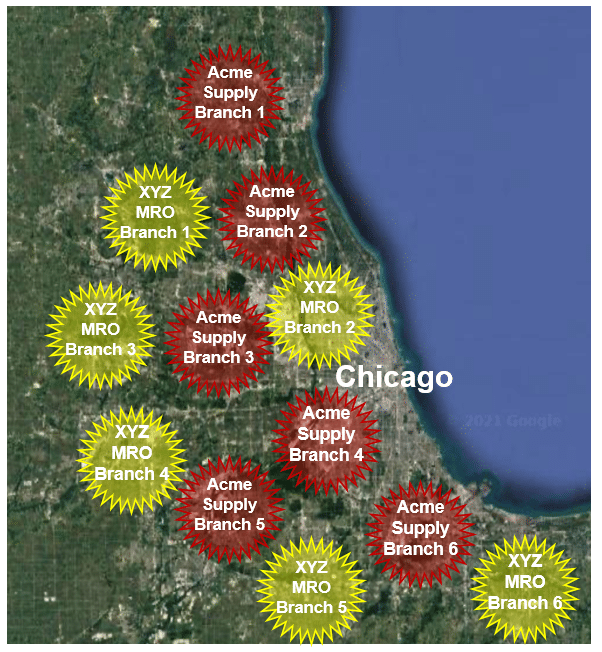

Master distributors can justify stocking a broader assortment even than Acme’s own distributor center because they aggregate demand from many distributors and branches. For example, if Acme Supply has two competitors called XYZ MRO and Denny Distribution, a master distributor serving all three companies would have many more SKUs that turn 3X per year than any of these firms individually.

There may be 100,000 MRO SKUs that sell 3X or more each year in Chicagoland, but each distributor serves only a small piece of the market, so none of them can justify stocking more than a few thousand products in each location. But master distributors can stock the rest of them because they are aggregating the demand of all of Chicagoland and not just one distributor’s service area or market share.

This is how master distributors add value in supporting B2B customers and how they earn their margins. They allow distributors to enjoy access to a nearly “endless assortment” to meet the demand of end customers.

How Marketplaces Change the Game

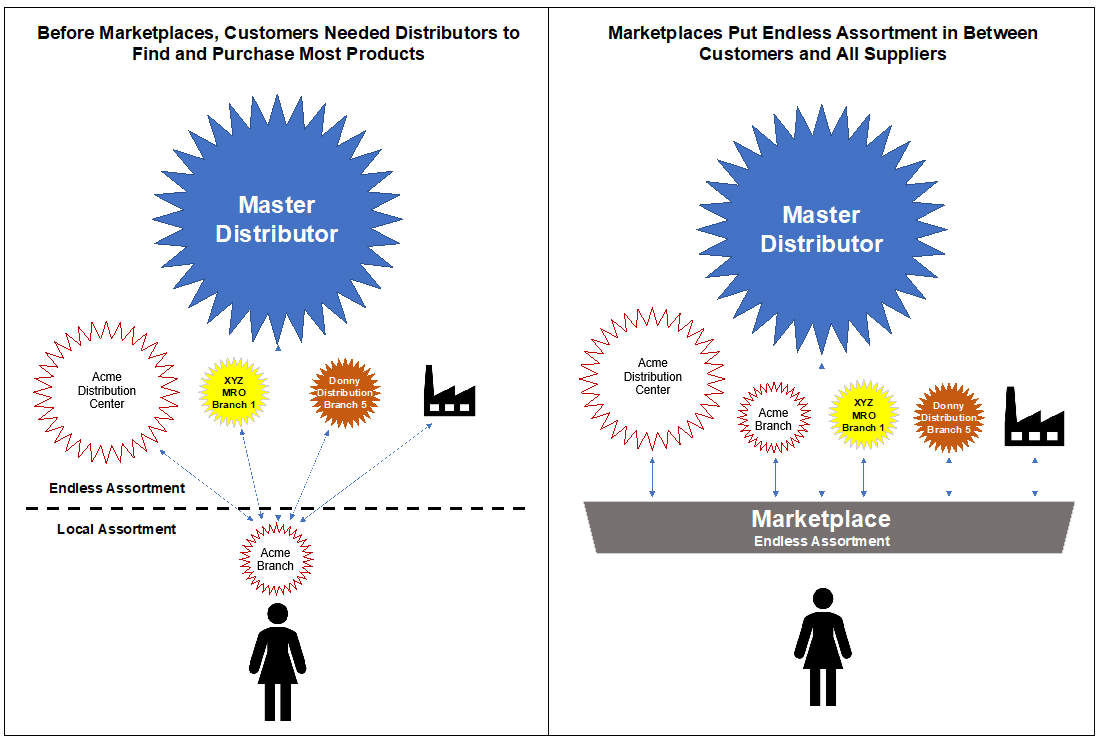

Business buyers love endless assortment. Unlike consumers, business buyers never shop recreationally. They need to find products and services as efficiently as possible. Before ecommerce, buyers typically called local distributors to find what they needed.

As distributors built ecommerce capabilities, buyers used many methods to find and purchase products. Some customers went to individual websites; others built out eprocurement systems with custom catalogs. The days of the “hard-to-find” product began to disappear; as long as you knew the product you were looking for, you could find it online, somewhere, although you often had to visit many websites to do it.

However, as marketplaces became more robust, comprehensive and common, they began to take enormous amounts of share – from retailers and distributors. A growing number of business buyers found they could consolidate POs, purchase efficiently and find everything in one place by switching from company-specific websites to marketplaces.

This has changed the value proposition for all the players in the channel because now customers have direct access to “endless assortment.” Distributors are no longer the gateways customers must interact with to locate products. Master distributors are further disadvantaged because their most fundamental value-add – vast assortment – has been commoditized.

Marketplaces thus represent an existential challenge for master distributors. In the next article in this three-part series, we’ll look at one: Berkshire eSupply. This master distributor has developed a unique strategy in which it arms independent distributors with their own ecommerce sites and access to about 1.2 million SKUs.

We’ll explore the effectiveness of this strategy and compare it with B2B marketplaces like Amazon Business. Does the Berkshire eSupply model offer an attractive alternative to marketplaces for distributors and end customers?

We’ll also take a look at Varis – the Amazon Business competitor that ODP Corporation (formerly Office Depot) is building. Can Varis differentiate effectively from Amazon Business? Is it possible for each of these enormous players to take their own share in B2B distribution, and what are the implications for other distributors?

Next: Part 2: From Master Distributors to Marketplaces: Berkshire eSupply is an “Upside Down” Marketplace

**All distributor names we mention are chosen randomly; any similarity to real companies by name, locations, capabilities or otherwise is accidental.

Ian Heller is the Founder and Chief Strategist for Distribution Strategy Group. He has more than 30 years of experience executing marketing and e-business strategy in the wholesale distribution industry, starting as a truck unloader at a Grainger branch while in college. He’s since held executive roles at GE Capital, Corporate Express, Newark Electronics and HD Supply. Ian has written and spoken extensively on the impact of digital disruption on distributors, and would love to start that conversation with you, your team or group. Reach out today at iheller@distributionstrategy.com.