Berkshire eSupply: Evolution and Current Offering

In 2017, Berkshire Hathaway acquired Production Tool Supply (PTS), a 65+-year-old Michigan-based distributor and master wholesaler.1

The distributor part of the company is called, PT Solutions. The “master wholesaler” division was rebranded, Berkshire eSupply. PTS had long operated as a master wholesaler, providing inventory availability and marketing services like private-label catalogs and flyers along with drop-shipping to other distributors.

But over the years, the company has radically updated its value proposition. For example, a distributor can pay a nominal sum to Berkshire eSupply to build a dedicated, custom-branded website with the option to add up to 2 millions SKUs. When the distributor’s customers order these products, eSupply fulfills them from three distribution centers or its supplier partners. Distributors can add their own local SKUs as well.

Many smaller distributors cannot afford state-of-the-art eCommerce capabilities, nor can they offer their customers a 2 million-SKU assortment. In an in-depth interview with Industrial Distribution in March/April 2020, eSupply CEO John Beaudoin described his company’s new “BESN” (Berkshire eSupply Network):

“The build-out is going to lead to higher fill rates and a fast-paced market to the end customer via the distributor. We’re going to be a fulfillment partner. We want to be a web partner. We’re also going to be a logistics and ‘e-chain’ partner all the way through the pipeline. The technology is the equalizer, and the people at eSupply really create the moat — something that gives each independent distributor extra product expertise, extra fulfillment capabilities and more margin that leads to the kind of profit they wouldn’t be able to achieve on their own.”

This value proposition gives small distributors a variety of capabilities, including a way to get a good website with a wide range of products and good searching and buying capabilities at a low cost. Berkshire eSupply benefits by making its products available on hundreds (and potentially thousands) of websites operated by small and midsize industrial distributors.

It’s a great plan, except for three big problems.

Three Obstacles to Berkshire eSupply’s Success

1. Small and midsize distributors have proven to be very poor at driving eCommerce sales.

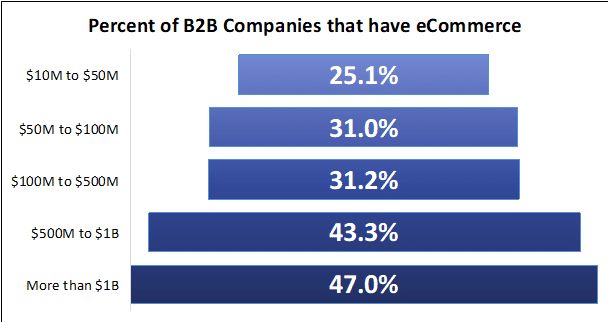

Every year, we conduct the most comprehensive survey of distributors exploring their eCommerce performance. In our last survey, 108 respondents worked for distributors that seemed to be in Berkshire eSupply’s target market: $10M to $50M in annual revenues and in a durable goods category like hardware, industrial supplies, safety, etc.

These distributors reported that their 2019 websites generated, on average, only 5.4% of their sales. While it’s likely these customers saw this percentage grow during the pandemic; it’s also likely that their more digitally capable competitors grew faster. In other words, we believe these companies lost eCommerce share over the last two years.

The upside for these companies is relatively limited. Our research shows that only 25.1% of companies like this even have eCommerce – 75% of similar companies don’t sell online at all.

While you could argue that this is a good hunting ground for Berkshire eSupply, it’s obviously going to be a long time before these distributors become experts at driving sales through their websites.

Berkshire eSupply isn’t the only master wholesaler investing resources in helping customers build digital capabilities. Earlier this week, Orgill Hardware – which supports distributors, retail hardware stores, etc. – announced it had fully attributed 1 million SKUs for customers to use in their “e-commerce websites, point-of-sale (POS) systems or in a variety of other functions.” Interestingly, Orgill only sells 12.5% of these SKUs; it attributed the rest as a service to their customers.

Both master wholesalers may yield a return on these investments. After all, their customers have nowhere to go but up when it comes to growing their online revenues. But there’s another problem brewing for this channel – it’s losing overall share to a rival business model.

2. Business buyers, like consumers, are rapidly turning away from company-specific websites and are buying from marketplaces instead.

In the first article in this series, we discussed how marketplaces had taken the core benefit of master distributors – “endless assortment” – from behind the distributor to in front of the customer. This is one of the reasons that marketplaces are taking share in B2C and B2B markets at a breathtaking rate.

Digital Commerce 360 says that “online marketplaces accounted for nearly two-thirds —62.5% — of global ecommerce in 2020, up from 60.1% the year before” and that “nearly 40% of business buyers make at least 26% of all corporate purchases on Amazon Business.”

Research we conducted at Distribution Strategy Group uncovered that manufacturers are planning on an enormous channel shift: they expect to get nearly 20% less of their sales through traditional distributors in five years while digital channels will grow by about 80%.

Data shows that business customers are increasingly buying from a small number of large websites, while Berkshire eSupply’s model relies on a large number of small websites. Other master distributors face similar challenges, of course, but are less focused on their distributor customers’ eCommerce channels.

In our work, we speak with executives from manufacturing companies regularly and the story is the same: they’re doubling down on marketplaces and expecting sales through traditional distributors to continue to decline. One large manufacturer told us their sales through Amazon and Amazon Business are up about 80% over the prior year while their sales to eSupply have declined for two years in a row. While this is likely not representative, we believe the overall trend strongly favors Amazon.

To be clear, we believe there are good growth alternatives for Berkshire eSupply, and we will explore those in the third article in this series. But the company’s current focus on collaborating with smaller distributors to help them build out their eCommerce channels faces an uphill battle.

It’s also a financial model that gives away the most precious aspect of a marketplace: growth without variable expenses.

3. Berkshire eSupply’s model foregoes the major financial benefits of a marketplace.

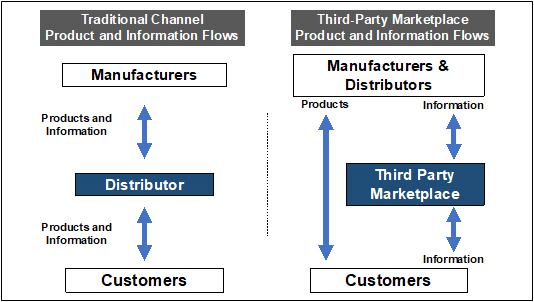

Marketplaces like Amazon Business and Zoro scale profits with no variable costs because they keep the digital aspects of transactions while pushing the physical parts of the sale to their third-party sellers. They achieve this favorable relationship by splitting the product and information flows from the manufacturer to the customer.

Traditionally, manufacturers would ship products to distributors, who would then make them available to customers. Information – product data, images, marketing copy, transaction data, etc. – was similarly shared between players.

Marketplaces split these flows. They keep the information flows and put the responsibility for product flows onto their third-party sellers. The information flows can be standardized, automated and digitized. Once a marketplace platform is built, the owner can add products to it and enjoy sales commissions without incurring variable costs as they grow.

The product side is a different story. You can’t digitize working capital (e.g., inventory) and you have to pay people to pick, pack and ship orders. Utility and security costs for warehouses can be considerable. Product flows have inescapable variable expenses.

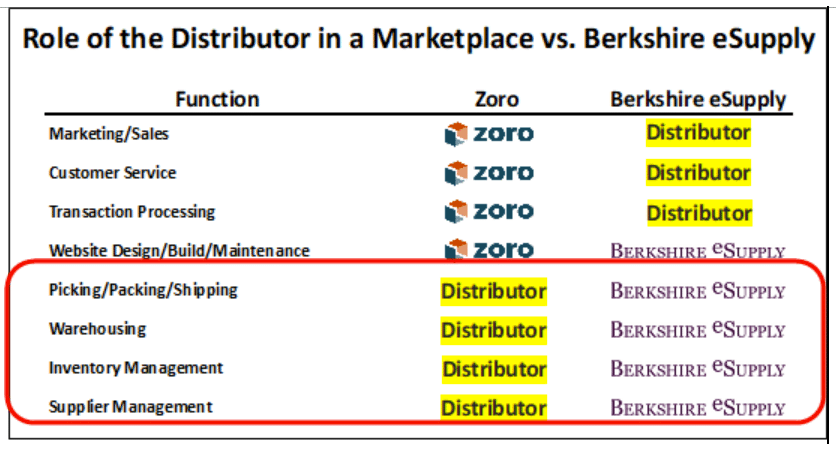

Berkshire eSupply’s strategy turns the traditional notion of a marketplace on its head. Consider how responsibilities are split between Berkshire eSupply and its distributor partners vs. a traditional marketplace and its third-party sellers. We use Zoro as an example, but the same characteristics apply to distributors in all traditional marketplaces, including Amazon Business, Walmart Marketplace, etc.

Most of the variable costs in the relationships shown in this graphic are contained in the activities circled in red. Marketplaces hand these off to their third-party sellers, while Berkshire eSupply is the third-party seller for its distributors. Berkshire’s approach basically turns every distributor into a type of mini marketplace.

Another potential challenge is that marketplaces ensure that they own the customer relationship and hold the third-party seller at arm’s length. In Berkshire eSupply’s case – as the third-party seller – the company also does not own the customer. Of course, master distributors have never owned the end customer relationships. The problem is that distribution channels are evolving rapidly, and master distributors need to formulate new value propositions and strategies. It’s hard to do that when you have little information about the end customers for your products.

Where does Berkshire eSupply go from here?

When I talk to people about Berkshire eSupply, I often hear, “With all that Berkshire money, eSupply should be able to take on anyone – including Amazon.” But I suspect the performance expectations for Berkshire Hathaway companies are similar to what I experienced in my turns as an executive for five publicly held companies: If you want the capital, you’d better have a good business case and a track record of success.

Fortunately, Berkshire eSupply has some exciting growth prospects. While I believe its current strategy faces some serious obstacles, I don’t believe that tens of thousands of distributors are going out of business soon or that they will all fail at eCommerce. Some of them are no doubt highly successful with eSupply, and there will be more in the future.

But I think this strategy considerably under optimizes the potential of Berkshire eSupply’s core capabilities. I also think another major player is a natural partner for eSupply. That company might need eSupply as badly as eSupply needs them.

That will be the subject of the third installment in this series.

Ian Heller is the Founder and Chief Strategist for Distribution Strategy Group. He has more than 30 years of experience executing marketing and e-business strategy in the wholesale distribution industry, starting as a truck unloader at a Grainger branch while in college. He’s since held executive roles at GE Capital, Corporate Express, Newark Electronics and HD Supply. Ian has written and spoken extensively on the impact of digital disruption on distributors, and would love to start that conversation with you, your team or group. Reach out today at iheller@distributionstrategy.com.