When Managed Properly, Small Customers Can Be Served Profitably

Companies typically start with small customers, grow some of them into large customers, continue to add new small customers and learn a lot from serving all of them.

Small customers are an important source for learning how to serve myriad market needs. They diversify the customer base (and associated risks of customer concentration) and, in aggregate, improve pricing leverage with more powerful customers and vendors. They also can represent a leading indicator of a company’s sales and marketing vitality, its operational capabilities and, more fundamentally, the validity of a company’s value proposition and competitive positioning. A healthy business will likely have a continuous flow of small customers. It’s exciting, at a gut level, to attract new small customers.

So, why do so many executives feel ambivalent about small customers? If you ask them to describe their customer base, they almost always start off by using the 80/20 rule and tell you about everyone in the top 80 percent and nothing about those in the bottom 20 percent. They treat the bottom tier as if it were nonexistent, not worth understanding, not worth managing.

This perspective has consequences.

First, there are plenty of reasons to be cautious about small customers and their profitability. Small customers are a challenge to serve profitably. There is a lot of churn with small customers, many of whom buy one time and then disappear. Their up‐front costs to serve, as a share of available gross profit, are high. They can consume valuable organizational bandwidth, reducing service levels, implied future growth rates and pricing leverage for larger accounts.

Small customers may distract the sales team from targeting the bigger customer opportunities that drive profitability. Additionally, typical sales commission structures pay a higher share of potential profit than they would if small customers’ relatively greater costs were properly understood.

Small customers may be more prone to haggle on price, and they frequently receive discounts that many executives would consider unacceptable for larger accounts. It’s no surprise that many management teams are cautious of the value small customers provide. Every business should understand these factors carefully and be thoughtful about how and when to pursue small customers.

Small Customer Turnover

Many small customers are one‐time customers. They often buy a product once, often as a convenience purchase, and never buy from you again – presumably reverting to their usual supplier. They churn at a very high rate.

“Churn” is the percentage of accounts that have sales in a given 12‐month period but do not have sales in the following 12‐month period. Strategic Pricing Associates data show the discouraging difference in small‐customer churn: There is a 30 percent to 40 percent churn rate in small customers (defined as the bottom quintile, or 20 percent, of revenue), compared to 3 percent to 6 percent churn in the higher quintiles.

Setting up accounts for a one‐time event is expensive and time‐consuming. It requires entering new customer information in the CRM, finding product from bottom‐tier vendors (also more costly to serve), understanding new specification and application requirements, and processing credit and payment activities.

For the typical distributor, these setup costs are broadly estimated at $50 to $75, lowering the profitability for virtually all small one‐time customers. Furthermore, small customers’ order volumes are also small, frequently less than break‐ even revenue. Any order below $250 from such a customer is likely to be unprofitable if properly measured. SPA estimates the impact of these money‐losing orders at about 50 basis points on overall revenue.

Inside and outside sales reps waste time, effort and focus on accounts that provide the superficial gratification of new business but that are actually reducing profits. The commission structure likely rewards them on either sales dollars or (overstated) gross margin dollars.

The Myth of “Growth Potential”

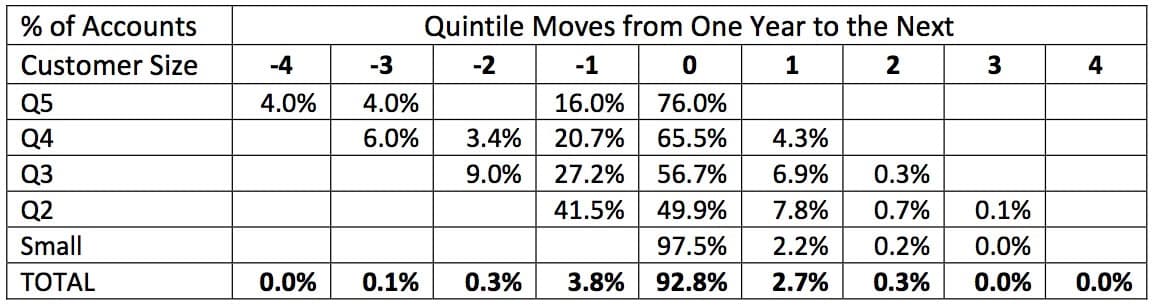

Sales reps often misunderstand the true potential of small accounts, labeling them “high potential.” SPA’s research shows that in any given year, 93 percent of accounts stay in the same size class the following year. Furthermore, 97.5 percent of small accounts in any given year remain small the next year; 4 percent move up one quintile; 1 percent move up two quintiles; 0 percent move up three or four quintiles.

The upward mobility statistics are modest but better for other customer size quintiles. The biggest opportunities seem to be concentrated in retaining and/or expanding the loyalty of the next two quintiles up in size; in these groups, there is a 30 to 40 percent probability that they will shrink by one or two quintiles from one year to the next. Sales efforts should be prioritized accordingly.

The real growth opportunities are concentrated in Table 1.

Underpricing of Small Customers

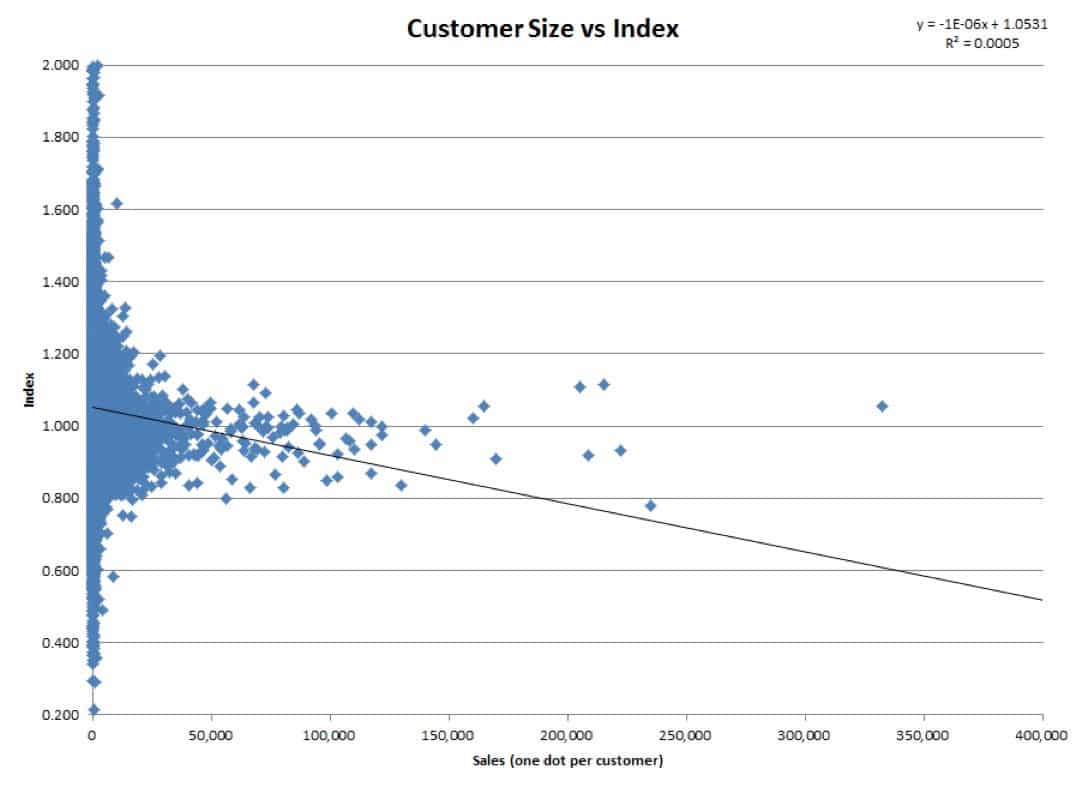

The tendency of small customers to receive lower prices cannot be overstated and shouldn’t be ignored. SPA’s research shows that 30 percent of small customers in any given year are paying below‐market price for their basket of products, reducing overall margins by 3.5 percent to 5.5 percent. To measure the margin impact, we compare actual margin to what it would have been if customers had paid true market price and/or size‐adjusted market pricing.

Small customers often get lower prices for several reasons. First, the small dollar impact of large pricing concessions to small customers doesn’t trigger the financial alarm bells that would result if the same percentage concessions were given to larger customers. This is called financial death by a thousand small price cuts. This disparity in demonstrated in Figure 1 below.

Many small accounts, because they are new to the ERP system, get priced on‐the‐fly, side‐stepping pricing structures and safeguards. They aren’t tracked carefully due to their size and churn rates. Most importantly, their cumulative drag on financial performance is rarely fully understood.

The cumulative effect of small customers’ churn characteristics, disproportionate fixed costs and tendency to be underpriced conservatively total 4.2 percent of sales for the typical distributor, 0.4 percent for disproportionate churn characteristics, 0.4 percent for disproportionate up‐front costs and 3.4 percent for underpriced small customers. Since the average distributor makes only 4 percent EBITDA, the incremental costs of serving small customers represents an ongoing drain of more than 100 percent of average EBITDA. For a $50 million distributor, that reduction in EBITDA is $2.1 million annually, with an implied reduction of $14.7 million (at multiplier of 7x) in enterprise value. Managing small‐ customer profitability is indeed a million‐dollar challenge.

Are most distributors better off firing small customers and avoiding acquiring new ones? Shareholders will want to know the strategy to address these pivotal facts. These facts can be mitigated, setting the stage for true profitability (or, perhaps, just smaller losses) from the small customer base.

Manage What You Measure

First, establish a quantitative assessment of the issue in your business. Expert reporting and pricing tools can help quantify your small customer challenge:

- Document the percentage of revenue coming from small accounts.

- Identify churn rates by customer type and size.

- Profile vendor cost‐to‐serve and vendor mix per customer type/size tier.

- Identify and measure underpriced volume by customer type and size.

- Set up pricing tools and processes to remediate and prevent underpricing of small customers.

- Understand transactional cost‐to‐serve by customer type and size.

- Identify and quantify unprofitable customers.

- Properly adjust commission structures to reflect profitability characteristics.

- Quantify the financial drag on EBITDA and enterprise value.

These metrics and tools can help identify how to turn the profit situation around for both small customers and others.

A Path Forward

The key to happiness with small customers is complex yet simple. Refrain from exerting scarce organizational resources on small accounts that have little or no potential growth rates. Point them to methods of service (inside sales, e‐ commerce, etc.) and vendors that are appropriate to the size of the opportunity. Incent the sales team to reduce churn rates for mid‐size accounts and to identify and deliver profitable small accounts.

Most importantly, make sure small accounts are priced at reasonable premiums to offset their higher costs to serve. Make sure the pricing process and tools reliably produce this outcome.

Commit to making meaningful progress to boost the profitability of small accounts:

- Identify which customers are underpriced, by how much and on which products.

- Assign those customers to new, optimized pricing structures that mitigate or reverse the profit drag.

- Identify which customers must do business online or through other low‐cost transaction methods or suppliers.

- Set terms and conditions (minimum order size, payment terms, price tiers, vendor limitations) that improve profit drivers.

- Identify predictive factors to avoid churn‐prone small customers.

- Prioritize sales assignments to those small accounts with clear predictors of growth.

- Add important safeguards to commission structures to align incentives.

Distributors need to apply classic Six Sigma principles to define, measure, analyze, implement and control a small‐ customer strategy.

With a proper understanding of small‐customer profit and vitality characteristics, realistic expectations about their costs and benefits, and a strategy for managing both, a company can improve its vitality and profitability. The key is understanding, strategy, processes and execution. Instead of always thinking about the 80/20 principle, make a point of systematically inverting this perspective to the 20/80 principle.

Make small customers a profitable source of growing vitality. Shareholders will appreciate it.

As Chief Operations Officer of a Distribution Strategy Group, I'm in the unique position of having helped transform distribution companies and am now collaborating with AI vendors to understand their solutions. My background in industrial distribution operations, sales process management, and continuous improvement provides a different perspective on how distributors can leverage AI to transform margin and productivity challenges into competitive advantages.