When we ask executives for the value proposition of their business, they usually provide a ready, confident and well-rehearsed answer. The answer consists of a few claims about what they believe they do well. Overwhelmingly, these claims have been derived through executive intuition or anecdotal feedback from the sales rather than rigorous processes with market testing.

Furthermore, when asked about the economic benefit of their value proposition to the customer, almost none can provide an answer. Both of these phenomena indicate a fundamental lack of understanding about what truly constitutes value in distribution.

The importance of understanding and conveying value today has changed for several reasons:

- “Frugalnomics” and the economic buyer — Today’s buyers are overloaded, skeptical and frugal. Increasingly they look at a purchase through the lens of economic value, not just price.

- Multi-channel competition — The new competition to your field sales person might be another field sales person. But increasingly, that competition is from e-commerce and inside sales channels, as well. If your value proposition is dull, your competitors will take market share from you through these channels.

- Diminished role of relationships — When distribution was based primarily on relationships, the understanding of value was unimportant. Strong relationships drove buying behavior and could trump value. Today, the role of relationships is on the decline due to retirement, mergers and acquisitions.

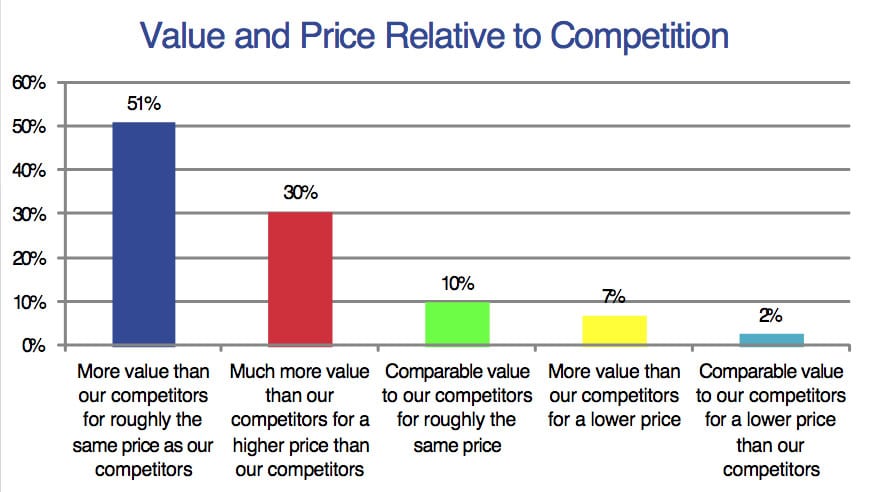

We recently conducted a survey with MDM regarding positioning and perceptions of value with 230 distribution executives and other management. Nearly 90 percent of distributor respondents believe that they deliver more value than their competitors. Many distributors perceive that they deliver superior customer service and expertise.

Value and Price

Respondents in the survey were asked to select the position that best describes their business from the following choices:

- We offer much more value than our competitors for a higher price than our competitors

- We offer more value than our competitors for roughly the same price as our competitors

- We offer more value than our competitors for a lower price

- We offer comparable value to our competitors for roughly the same price

- We offer comparable value to our competitors for a lower price than our competitors We offer less value than our competitors for a much lower price than our competitors

The results are shown in Figure 1 below. Only 12 percent of the respondents believe that they are delivering comparable value to competitors. The rest of the respondents believe that they are delivering much more value for a higher price, more value for the same price or more value for a lower price.

While it is true that, in an attempt to maintain price and retain customers, these respondents are delivering more value than before the downturn, so are other distributors. Clearly, it is impossible for the overwhelming majority to deliver more value than their competitors.

There is a concept called the “Lake Wobegon effect,” where almost all members of a group claim to be above average. It stems from a natural human tendency to overestimate one’s capabilities, and is named after the town in Garrison Keillor’s “Prairie Home Companion” radio show.

The characterization of the fictional location, where “all the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the children are above average,” has been used to describe a real and pervasive human tendency to overestimate one’s achievements and capabilities in relation to others. It has been observed in many different groups of people including CEOs, hedge fund managers, presidents, coaches, and radio show hosts, among others.

Operating Discipline

In “The Discipline of Market Leaders” by Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersema, they describe three different operating models that deliver value to customers:

- Product Leadership — In this model, companies focus on producing the best product. Companies who are most successful at this model are obsessed with innovation and reward the risks taken in the process. Example companies include Apple, 3M and General Electric. For distributors, this operating model is almost non-existent because they are selling products from other suppliers.

- Operational Excellence — This focuses on delivering the best total cost. Companies that choose this model are continually looking for ways to streamline operations and reduce cost. They abhor waste. Uniformity of the offering or product is the hallmark of such companies. Example companies include McDonalds, Southwest Airlines and Walmart. Distributors who excel in operational excellence tend to be larger and are very efficient with logistics.

- Customer Intimacy — Companies that focus on customer intimacy deliver the best total solution, often at a price premium to their customers. Customers choose them because they want the expertise, customer service and often high degrees of customization that this model delivers. Example companies include Nordstrom, CDW and Cable and Wireless. Many distributors pride themselves on aspects of a customer intimate model.

Companies that excel within one operating discipline have alignment of processes, culture, metrics, incentives and style to create specific value in that discipline. The result is a value proposition that is relevant to customers and not equaled by competitors. However, a key aspect of choosing one discipline is that the company maintains threshold standards in the other disciplines.

Performance in the other disciplines has to maintain the threshold level, otherwise it impairs the attractiveness of your unmatched value in the chosen operating discipline. So, a company may focus on customer intimacy, yet their logistics performance needs to meet a requisite level for them to compete. Similarly, an operationally excellent company needs to have a sufficient level of customer service to compete.

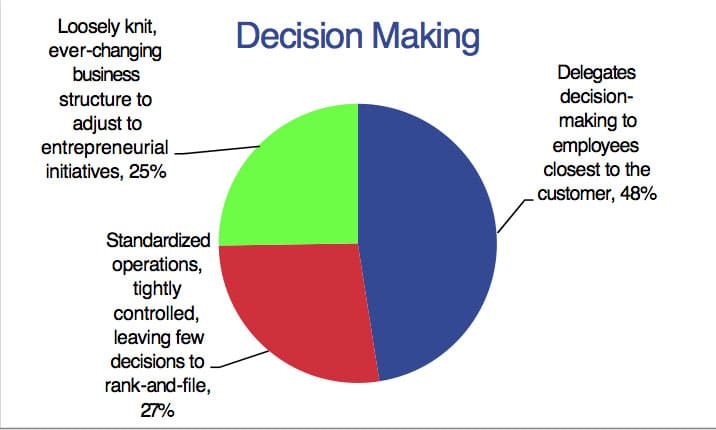

Because product leadership is not really an option for distribution, there are effectively only two operating disciplines in distribution: operational excellence and customer intimacy. In the survey, we asked respondents about their decision-making processes and their culture in order to place their companies into one of those two categories.

Decision-Making Style

One of the hallmarks of a customer-intimate company is that decisions are delegated to employees who are close to the customer. This allows them to customize solutions for specific customers. Nearly half of the respondents believe that their company delegates in this way.

Slightly more than a quarter of the respondents believe that decision making is characterized by standardized operations and tightly controlled; this is consistent with an operationally excellent model.

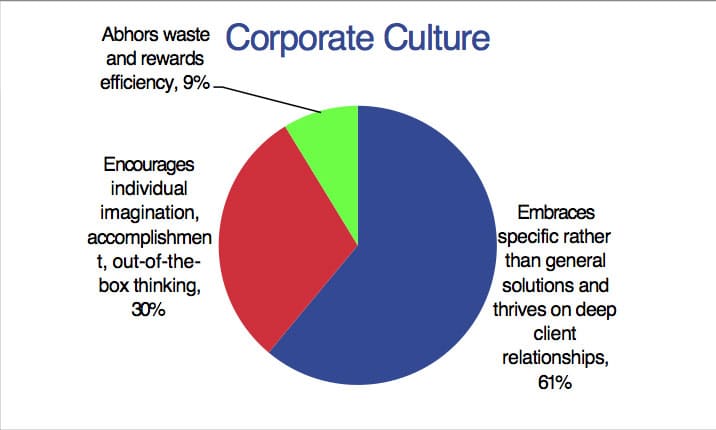

Corporate Culture

A key aspect in the corporate culture for customer-intimate companies is embracing specific rather than general solutions. The focus is on individual solutions for particular customers. It very much like the cliché employed by so many companies that says: “We measure success one customer at a time.” As shown in Figure 3, 61 percent of the respondents believe that their corporate culture fits this model.

The next most common choice about encouraging individual imagination is more closely aligned with product leadership. Only 9 percent of the respondents indicated that their corporate culture abhors waste and rewards efficiency which is aligned with operational excellence.

In the survey, we also asked respondents two open-ended questions:

- What does your company do better than any of your primary competitors?

- What do your primary competitors do better than you?

Almost no distributors perceive that they have a price advantage over their competitors, yet 37 percent believe that their competitor has a price advantage over them.

Forty-six percent believe their value proposition is about customer service and/or expertise; none of the respondents believe their competitor has an advantage over them in this area. Many of those who believe that they have superior customer service or expertise also believe that their competitor has a price advantage and will discount to win business.

Almost 20 percent believe their competitor has a sales and marketing advantage. The sales and marketing advantage can take the form of better e-commerce, more feet on the street, or a better brand. Several respondents felt that their competitor used unfair or misleading marketing tactics as an advantage, or “smoke and mirrors marketing.”

These last three points really underscore how much pride many distributors take in their own business and how they service customers. Yet, while many distributors correctly perceive their own business, their subjectivity results in a misperception and mischaracterization of the competition as ruthlessly efficient, cold, at times unethical, willing to discount to win business, and lacking the customers best interest at heart. This is similar to the Lake Wobegon Effect regarding perceptions of value and price.

Creating Value for Customers

Distributors have an opportunity to create value by better understanding what customers value. They also have an opportunity to clarify their operating discipline. The proper understanding of value and operating discipline can help propel distributors to higher margins and higher market share. Without a clear understanding, distributors are at a disadvantage in the new world of frugalnomics, multi-channel competition and erosion of relationships.

In the next article in this series, we will look at systematic approaches to understanding value and price and for determining the most appropriate operating discipline.

Jonathan Bein, Ph.D. is Managing Partner at Distribution Strategy Group. He’s

developed customer-facing analytics approaches for customer segmentation,

customer lifecycle management, positioning and messaging, pricing and channel strategy for distributors that want to align their sales and marketing resources with how their customers want to shop and buy. If you’re ready to drive real ROI, reach out to Jonathan today at

jbein@distributionstrategy.com.