In the first part of this series, we discussed the growing realization by distribution execs that customer consolidation can limit or even destroy operating profit for the firm. There has been considerable consolidation in industries that distributors serve resulting in Accounts of Unusual Size.

As a result, the number of customers is declining, but spend per customer, depending on the vertical sector, has increased. As accounts grow larger, they place greater pressure on distributors including demand for increased services, annual pricing agreements and financial incentives including terms and conditions of sale.

Activity Costing and the discipline of Customer Profitability have been around for over three decades in the distribution sector. Allocating operating expenses to customer activities yields a cost to serve an account and its associated operating profit.

Distributors, in the past, have managed customer profitability on an individual-account basis but seldom analyze the cumulative profits of their account portfolio. Simply ranking accounts by their percent of total activity profits (using an Excel Sort command from highest to lowest profit and totaling for a cumulative profit profile) finds that the distribution of operating income generated by accounts is: 20% of customers break even or have minimal profits; 40% of customers drive 130% to 140% of activity profits; and 40% of customers destroy 30% to 40% of activity profits.

The problem, as customers consolidate, is that many large revenue accounts destroy operating income. Hence, distributors find themselves selling more but destroying operating profits as large accounts place excessive demands on distributor services and through competitive bidding.

Distributors need two key pieces of information to deal with the problem namely, a modern-day activity costing model and a decision framework to turn around activity-negative customers.

Evolution of Activity Costing Models

Initial activity costing models used customer activities and their associated drivers to allocate operating expenses. There were, however, multiple problems with these early models. They were complex; the activities and drivers were often custom definitions and were “estimates” of time and cost. The models did not review the effect of different transaction types on the profit picture, and they did not have a common algorithm. Because of their complexity and the ever-changing nature of distributor value offerings, the models were difficult and expensive to change. Many distributors gave up on the subject(s) of activity costing and management after several years of trying.

Modern-day activity models vary, but there’s a general realization that the models should include:

- Algorithms based on transaction types (Think non-stock, stock, direct, online, etc.)

- Cost buckets based on the accounting ledger that follows the cost-to-serve cycle (Purchasing, put-away, picking, shipping, sales, customer service, invoicing, collection, etc.)

- Labor coefficients for different parts of the service cycle that recognize labor by transaction type by cost bucket

- Adjustments for special services including repair, storage, onsite management and others

- Design, as much as possible, for lines and invoices to drive service cost allocation

- Exclusion of fixed or “long-step” costs in the model including branch overhead and executive base salaries

It is not unusual to find transaction-based models with 15 to 20 transaction types or more with differing labor coefficients by service operation. Most of these models can be done on spreadsheets before being designed into the ERP system.

Strategies for Activity-Negative Profit Customers of Unusual Size

It is one thing to have 1,000 activity-negative accounts that total $5 million in sales vs. one $5 million account that is activity negative and trending more negative with each passing year. In past Activity Management solutions, small accounts could be rendered activity positive (or less activity negative) with pricing or changes to the service strategy. With large accounts, which demand special services and pricing, cutting back on special services and/or increasing price are difficult to achieve.

Past solutions to activity-negative accounts have included “firing” the customer by slowly raising price and deleting services. For large and extra-large accounts, this is not recommended. Why? Often, the firm has developed special services for these accounts and can’t easily delete them if the account is resigned. Additionally, these accounts throw off large amounts of margin dollars in any one period which, in times of overcapacity, can contribute to fixed or larger step costs.

Ergo, we generally do not advise relinquishing a large activity-negative account unless the operating profit is dismal, increasing over time, and the customer is abusive.

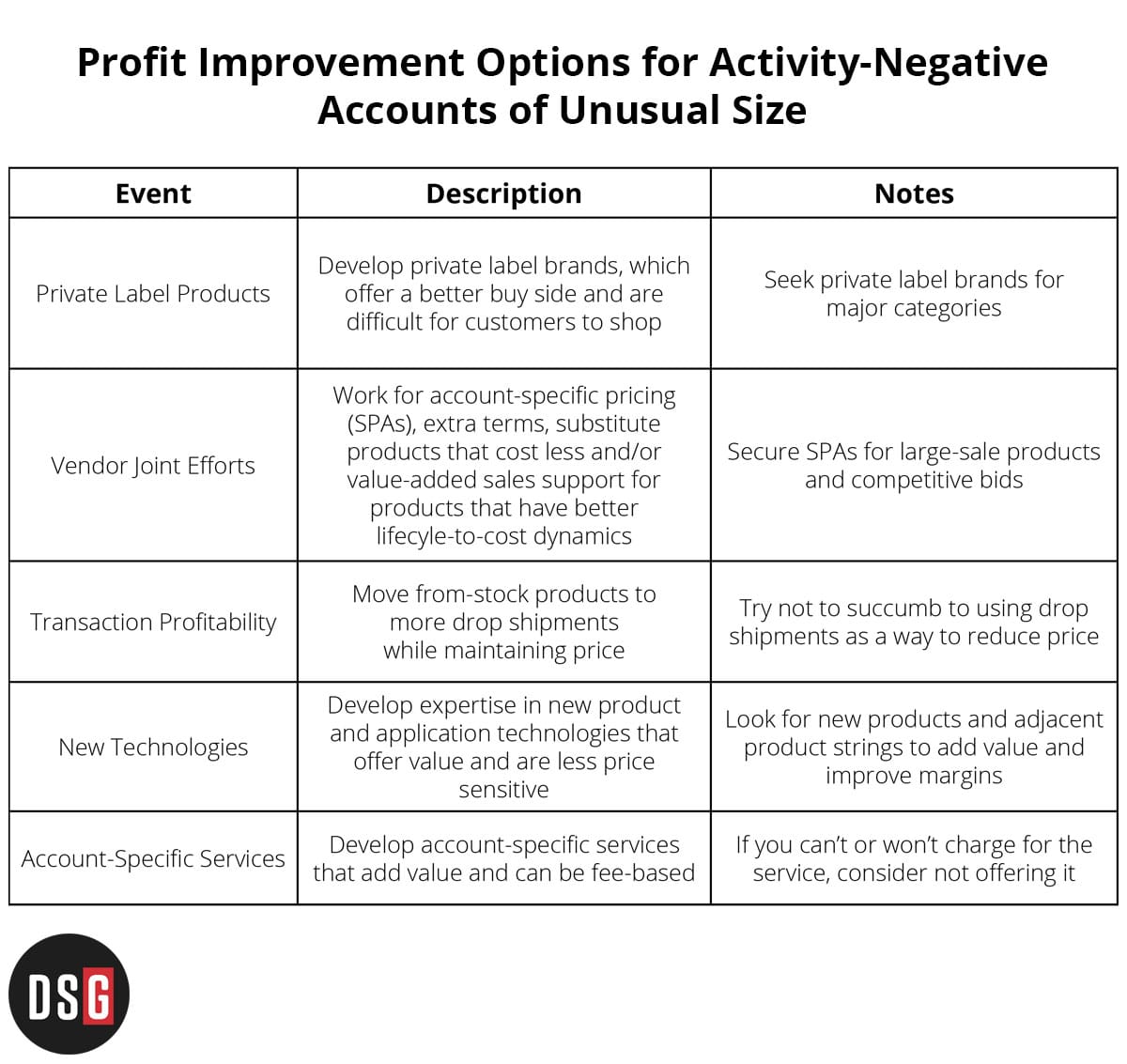

Exhibit I gives a decision table from our work on improving the profit picture of large, activity-negative accounts. The first action, one that we find vastly underrated, is the development of private label brands and offering them as substitutes. Private label brands often come with a price discount as compared to branded products of 20% or more. We typically find where private label brands yield 10% to 15% more than branded products, after discounting, to large/extra-large accounts.

Extra-Large/large accounts are often supported by joint vendor efforts inclusive of special pricing arrangements (SPAs), unique product attributes, special packaging and other custom offerings. When serving the demands of larger accounts, it is recommended that the distributor seek support from branded vendors for the unique requests of customers.

Transaction profitability and transaction profit mix are new subjects for distributors. The work follows using transactions as a basis for the activity costing model. For instance, account profitability can often be improved with drop shipments, but only if the customer is willing to handle the inventory from the vendor.

When pricing drop shipments, we find distributors often decrease the gross margin percentage. We discourage this practice; the decision to drop ship is one of efficiency and reduction in error for the customer. The reduction in processing costs by not sending the order through the branch network should be used to improve the activity profile of the customer.

New technologies and new application bundles are a great way to improve profitability. This involves working with key vendors on new products, getting them into customer trial, and evaluating their efficiency gains. New product introductions are, notoriously, poorly done by distributors. The primary reason for this is that distributors, who spend money and time on new products, are too often “rewarded” with added distributor competitors after successfully introducing the technology to the market.

However, our research and experience are consistent across the decades; distributors who launch new products, new technologies and develop new fee-based services have better organic growth. Over time, compounded organic growth allows the firm to hire better, more specialized managers and take share from firms who have lagged in new products and technologies.

The final means to differentiate and add value to demanding, extra-large/large accounts is in developing fee-based services. Often these services take investment in IT, extra capabilities and account-specific personnel. However, once successful, they become incredibly sticky. This accomplishes two outcomes: The account becomes less price sensitive on first cost as they realize the service value of intangibles and the costs of business development is reduced as the account becomes evergreen in nature.

Distributors who develop fee-based services should remember that reminding the customer of the value of custom services and maintaining their quality is important. Too often we find distributors who forget this and learn the lesson that services, while intangible, often trigger the account to shop new suppliers, if their quality and/or value is forgotten by the customer. Over time, services can become more valuable than the products the distributor sells.

The Future of Accounts of Unusual Size

Most of the markets that distributors serve are mature but growing. The demand for value in existing relationships is evident in new technologies launched in mature B2B markets and ongoing mergers and acquisitions. Consolidation in customers is integral to market growth, it mitigates redundancies and costs. As customers consolidate and place back-channel concessions on suppliers, wholesalers will need activity costing and a plan to change the relationship from first cost to a broader understanding and demonstration of value. Without activity costing and understanding the operating profit of extra-large/large customers, distributors can easily destroy value and do so at an increasing rate.

Scott Benfield is a consultant for B2B Manufacturers and Distributors. He is the author of six books and numerous research projects on B2B channels. He can be reached at benfield.scott@aol.com or (630) 640-5605.